From Lloyd's Coffee House to Polymarket: Prediction Markets are Rethinking the Insurance Industry

Author | Vinko

Editor | Sleepy.txt

In 2023, a letter arrived in the mailboxes of one hundred thousand families in Florida, USA.

The letter was from Farmers Insurance, a century-old stalwart of the insurance industry. The message was brief and brutal: one hundred thousand policies, covering everything from homes to cars, were being voided effective immediately.

A solemn promise on white paper turned into waste paper overnight. Angry policyholders flocked to social media, questioning the company they had trusted for decades. But all they received was a cold announcement: "We must better control our risk exposure."

Meanwhile, in California, things were even worse. Insurance giants like State Farm and Allstate had ceased accepting any new home insurance applications, and over 2.8 million existing policies were being denied renewal.

An unprecedented "insurance exodus" was unfolding in America. The insurance industry, once seen as a societal stabilizer, committed to providing a safety net for all, was now in turmoil.

Why? Let's look at the data below.

The damage caused by Hurricane Helene in North Carolina could exceed $53 billion; Hurricane Milton, according to Goldman Sachs' estimates, could result in insurance losses of over $25 billion; and a major fire in Los Angeles, as estimated by AccuWeather, could lead to total economic losses of $250 billion to $275 billion, with insurance payouts estimated by CoreLogic to be between $35 billion and $45 billion.

Insurance companies found themselves at the limit of their ability to pay claims. So, who could replace the traditional insurance industry?

The Wager in the Coffeehouse

The story begins over three hundred years ago in London.

In 1688, along the Thames River, in a coffeehouse named Lloyd's, sailors, merchants, and shipowners were all under the same shadow. Merchant ships laden with goods set sail from London to distant America or Asia. A successful return meant immense wealth, but encountering a storm, pirates, or a shipwreck meant financial ruin.

Risk, like a lingering dark cloud, hung over the head of every sailor.

The coffeehouse owner, Edward Lloyd, was a savvy businessman. He realized that these captains and shipowners needed more than just coffee; they needed a place to pool their risks. So, he began to encourage a form of "betting game."

A captain wrote down information about the ship and its cargo on a piece of paper, which he then posted on the wall of a coffee house. Anyone willing to take on some risk could sign their name on this paper and indicate the amount they were willing to insure. If the ship returned safely, they could share a proportionate part of the captain's payment (the premium); if the ship was lost, they would then be liable to compensate the captain for the losses.

When the ship returned, everyone rejoiced; when the ship sank, they shared the loss.

This was the prototype of modern insurance. It had no sophisticated actuarial models, only simple commercial wisdom—spreading one person's significant risk among a group of people to collectively assume it.

In 1774, 79 underwriters came together to form the Lloyd's Association, moving from the coffee house to the Royal Exchange. Thus, a trillion-dollar modern financial industry was born.

For over three hundred years, the essence of the insurance industry has remained unchanged: it is a business of managing risk. Through actuarial science, various risk event probabilities are calculated, risks are priced, and then sold to those seeking protection.

But today, this ancient business model is facing unprecedented challenges.

When the frequency and intensity of hurricanes, floods, and wildfires far exceed the predictive scope of historical data and actuarial models, insurance companies find that their measuring stick is no longer adequate to gauge the increasing uncertainty of the world.

They have only two choices: either substantially increase premiums or, as we have seen in Florida and California, retreat.

A More Elegant Solution: Risk Hedging

When the insurance industry is mired in the dilemma of "cannot calculate, cannot afford to pay, and dare not insure," we may consider stepping out of the insurance framework and looking for answers in another ancient industry: finance.

In 1983, McDonald's planned to launch a revolutionary product: the McDLT. However, a challenge loomed before the management—chicken prices were too volatile. If they locked in the menu price and chicken prices skyrocketed, the company would face huge losses.

The tricky part was that there was no chicken futures market available at that time for risk hedging.

Ray Dalio, then a commodities trader, provided a genius solution.

He said to McDonald's chicken supplier, "Isn't the cost of a chicken just chicks, corn, and soybean meal? The price of chicks is relatively stable, with the real fluctuations being in corn and soybean meal prices. You can buy futures contracts for corn and soybean meal on the futures market to lock in production costs. This way, wouldn't you be able to provide McDonald's with a fixed price for chicken?"

This "synthetic futures" concept, which seems completely normal today, was revolutionary at the time. It not only helped McDonald's successfully launch the McRib, but also laid the foundation for Ray Dalio to later create the world's largest hedge fund—Bridgewater.

Another classic example comes from Southwest Airlines.

In 1993, the then CFO Gary Kelly began implementing a fuel hedging strategy for the company. From 1998 to 2008, this strategy saved Southwest Airlines approximately $3.5 billion in fuel costs, equivalent to 83% of the company's profits during the same period.

During the 2008 financial crisis, when oil prices surged to $130 per barrel, Southwest Airlines used futures contracts to purchase 70% of its fuel at a locked-in price of $51 per barrel. This made it the only mainstream U.S. airline at the time able to sustain a "free baggage policy."

Whether it's McDonald's chicken or Southwest Airlines' fuel, they both reveal the same simple business wisdom: through the financial market, transform future uncertainty into today's certainty.

This is hedging. Its goal converges with insurance, but the underlying logic is completely different.

Insurance is risk transfer. You transfer risks (like car accidents or illnesses) to an insurance company and pay premiums for it; hedging is risk offsetting.

If you have a position in the spot market (e.g., need to buy fuel), you establish the opposite position in the futures market (e.g., buy fuel futures). When the spot price rises, the profit from the futures can offset the loss in the spot market.

Insurance is a relatively closed system dominated by insurance companies and actuaries; whereas hedging is an open system collectively priced by market participants.

So, since hedging is so elegant and efficient, why can't we use it to solve today's insurance industry challenges? Why can't a Florida resident hedge against the risk of a hurricane landfall like Southwest Airlines?

The answer is simple: because such a market does not exist.

It wasn't until a young man who started in a bathroom brought it to us.

From "Risk Transfer" to "Risk Trading"

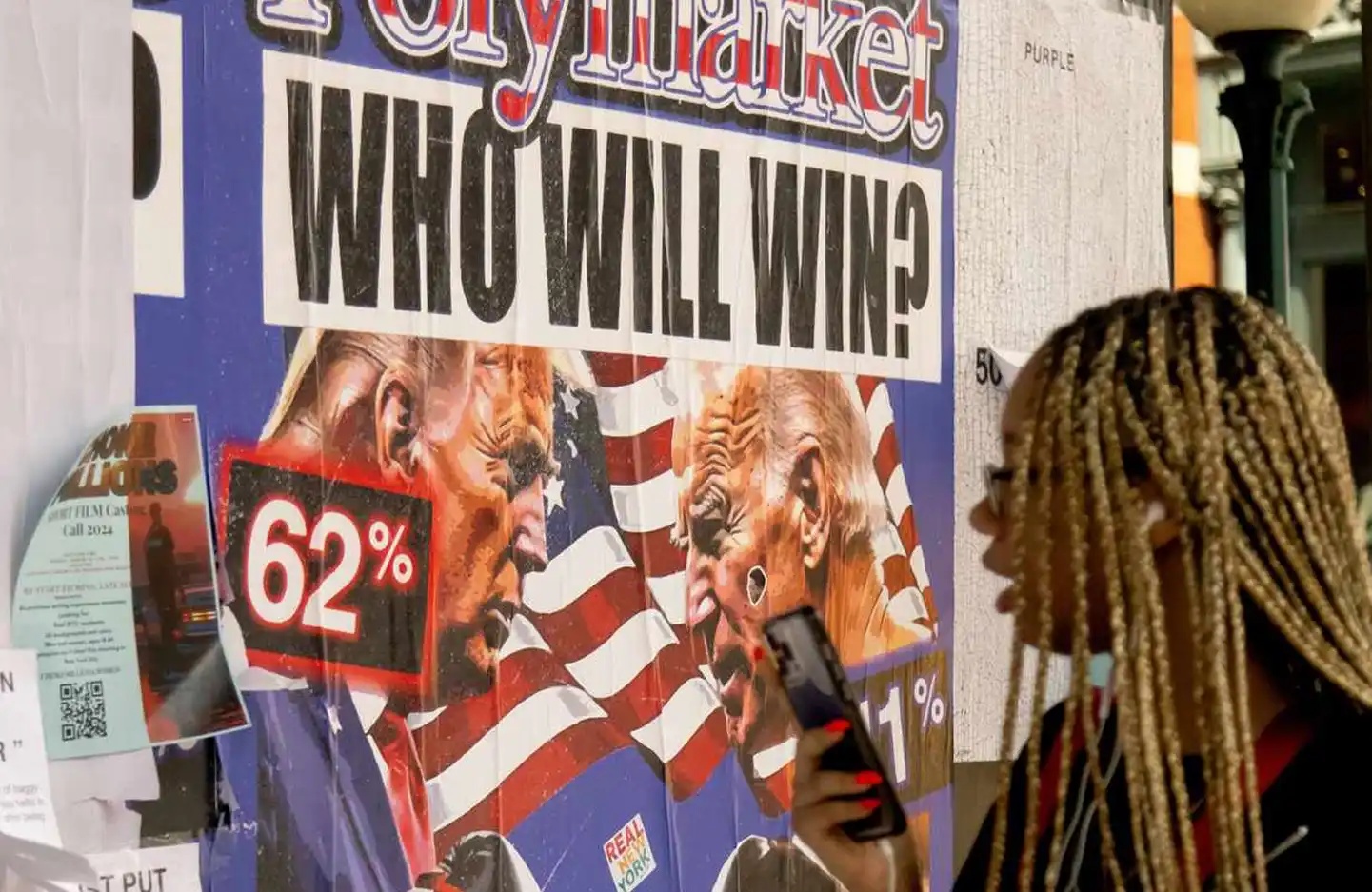

22-year-old Shayne Coplan founded Polymarket in a bathroom. This blockchain-based prediction market rose to fame in 2024 due to the U.S. presidential election, with an annual trading volume exceeding $9 billion.

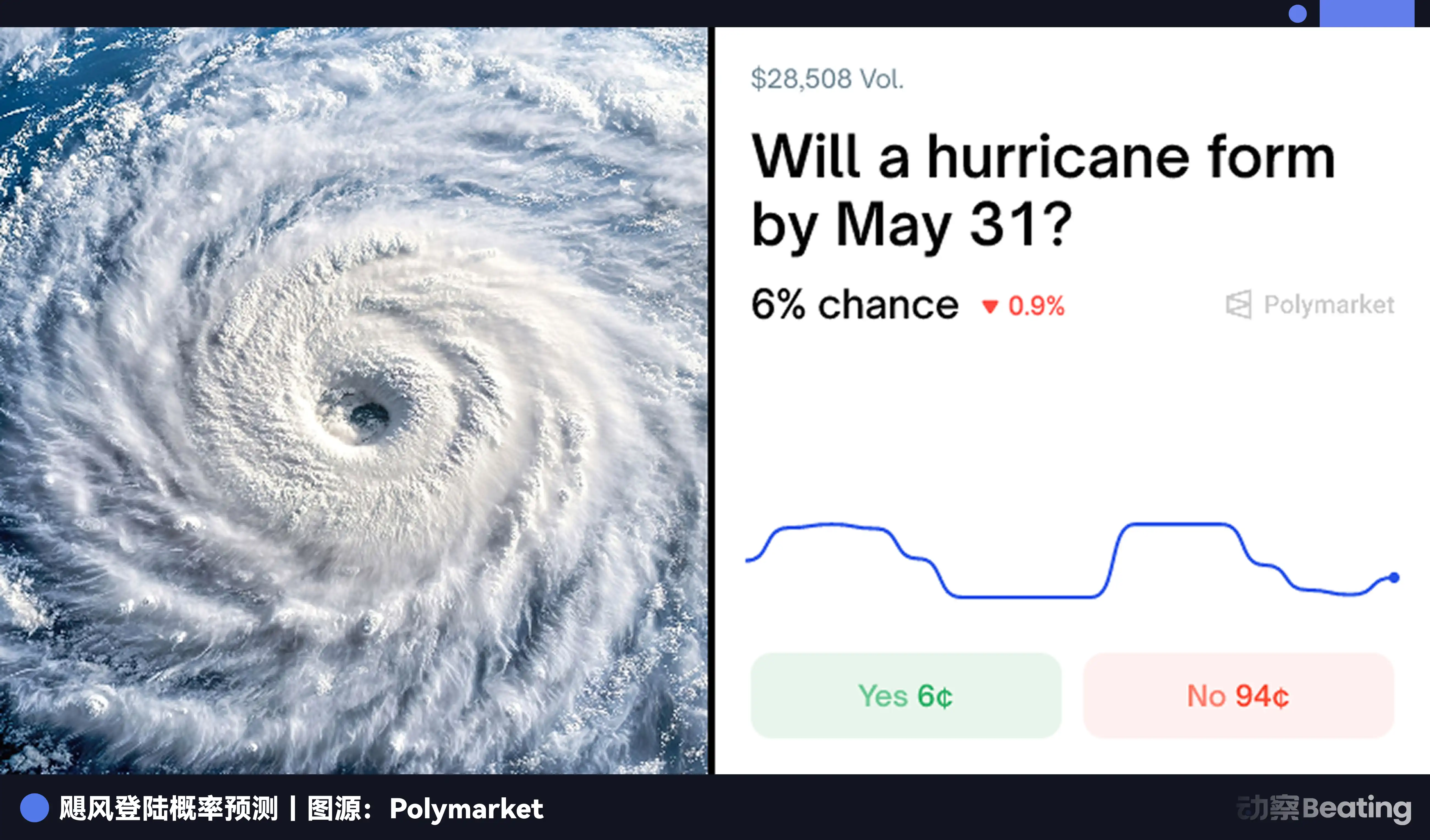

In addition to those political betting markets, Polymarket also has some interesting markets. For example, will Houston's highest temperature in August exceed 105 degrees Fahrenheit? Will California's nitrogen dioxide concentration this week be higher than average?

An anonymous trader named Neobrother accrued over $20,000 in profits by trading these weather contracts on Polymarket. He and his followers are known as the "Weather Hunters."

While insurance companies were fleeing Florida due to the unpredictability of the weather, a group of mysterious players was enthusiastically trading a 0.1-degree temperature difference.

Prediction markets are essentially a platform for "futurizing everything." They have taken the functionality of traditional futures markets, which dealt with standardized commodities (such as oil, corn, and forex), and expanded it to any event that can be publicly and objectively verified.

This has provided us with a new way to tackle the challenges of the insurance industry.

Firstly, it replaces expert arrogance with collective wisdom.

Traditional insurance pricing relies on the actuarial models of insurance companies. However, as the world becomes increasingly unpredictable, models based on historical data begin to fail.

In contrast, the price in prediction markets is "voted" on by thousands of participants using real money. It reflects the market's collective information on the probability of an event occurring. A contract regarding "Will a hurricane make landfall in Florida in May" sees its price fluctuation as the most sensitive and real-time measure of risk.

Secondly, it replaces the resignation to losses with the freedom to trade.

If a resident of Florida is worried about their house being destroyed by a hurricane, they no longer have just the option to "buy insurance." They can go to the prediction market and buy a contract on "Hurricane Will Make Landfall." If a hurricane indeed arrives, the profit from their contract can help cover the expenses of the damaged house.

Essentially, this is a form of personalized risk hedging.

More importantly, they can also sell this contract at any time to lock in profits or stop losses. Risk is no longer a heavy burden that needs to be bundled up and transferred all at once but has become an asset that can be sliced, traded, bought, and sold at any time. They have transformed from risk bearers to risk traders.

This is not just a technical improvement but also a mindset change. It liberates the pricing of risk from the hands of a few elite institutions and returns it to everyone.

The Endgame of Insurance: A New Beginning?

Will the prediction market, this "universal risk exchange platform," replace insurance?

On one hand, the prediction market is eroding the foundation of the traditional insurance industry in a disruptive way.

The core of the traditional insurance industry is asymmetric information. Insurance companies have actuaries and massive data models; they need to have a better understanding of risk than you to price it. But when the pricing of risk is replaced by a market that is open, transparent, driven by collective wisdom, and even insider information, the information advantage of insurance companies evaporates.

Florida residents no longer need to blindly trust insurance company quotes; they just need to look at the price of a hurricane contract on Polymarket to understand the true market assessment of risk.

More importantly, the traditional insurance industry operates on a "heavy model" — sales, underwriting, claims adjustment, claims processing... Each step is filled with labor costs and friction; whereas the prediction market is an ultimate "light model," with only trading and settlement, almost eliminating intermediate steps.

On the other hand, we see that the prediction market is not omnipotent and cannot completely replace insurance.

It can only hedge against objectively definable and publicly verifiable risks (such as weather, election results). For those more complex and subjective risks (such as accidents caused by driving behavior, personal health conditions), it proves to be inadequate.

You cannot create a contract on Polymarket for the whole world to predict "whether you will have a car accident next year."

Personalized risk assessment and management remain the core strengths of the traditional insurance industry.

The future landscape may not be a winner-takes-all battle of replacement but rather a new and subtle relationship of competition and cooperation.

The prediction market will become the infrastructure for risk pricing. Like today's Bloomberg Terminal and Reuters, it will provide the most basic data anchor for the financial world. Insurance companies may also become deep participants in the prediction market, using market prices to calibrate their models or hedge against catastrophic risks they cannot bear.

Insurance companies, on the other hand, will return to the essence of service.

When the pricing advantage is no more, insurance companies must rethink their value. Their core competitiveness will no longer be information asymmetry but will be more focused on areas of risk that require deep involvement, personalized management, and long-term service, such as health management, retirement planning, and wealth succession.

The behemoths of the old world are learning the dance of the new world. And the explorers of the new world also need to find the route to the old world continent.

Epilogue

Over three hundred years ago, in a London coffee house, a group of merchants invented a mechanism based on the most primal wisdom: risk mutualization.

Over three hundred years later, in the digital realm, players are reshaping the way we deal with risk.

History always inadvertently completes its cycle.

From compelled trust to free transactions. This may be another thrilling moment in financial history. Each of us will evolve from a passive risk acceptor to an active risk manager.

And this is not only about insurance; it is more about how each and every one of us can better survive in this world full of uncertainty.

Welcome to join the official BlockBeats community:

Telegram Subscription Group: https://t.me/theblockbeats

Telegram Discussion Group: https://t.me/BlockBeats_App

Official Twitter Account: https://twitter.com/BlockBeatsAsia