In 3 days, Ethereum will undergo these major changes

Original Article Title: Ethereum Fusaka Hard Fork: What's Changing?

Original Article Author: Sahil Sojitra

Original Article Translation: Golem, Odaily Planet Daily

The Fusaka hard fork, scheduled to be activated on December 3, 2025, is another major network upgrade for Ethereum following Pectra, signaling another important step towards scalability for this crypto giant.

The EIP of the Pectra upgrade focused on performance improvements, security, and developer tools. The EIPs of the Fusaka upgrade focus on scalability, opcode updates, and execution security.

PeerDAS (EIP-7594) enhances data availability by allowing nodes to validate Blob without downloading all data, increasing data availability. Several upgrades also enhance execution security, including limiting ModExp (EIP-7823), limiting transaction gas limits (EIP-7825), and updating ModExp Gas cost (EIP-7883). This Fusaka upgrade also improves block generation through a deterministic proposer lookahead mechanism (EIP-7917) and maintains Blob cost stability by introducing a "reserve price" tied to execution costs (EIP-7918).

Other enhancements include limiting block size in RLP format (EIP-7934), adding a new CLZ opcode to increase bitwise operation speed (EIP-7939), and introducing the secp256r1 precompile (EIP-7951) for better compatibility with modern cryptography and hardware secure keys.

Fusaka is a combination of Fulu (execution layer) and Osaka (consensus layer). It represents another step for Ethereum towards a highly scalable, data-rich future, where Layer 2 Rollups can operate at lower costs and faster speeds.

This article will delve into the 9 core EIP proposals of the Fusaka hard fork.

EIP-7594: PeerDAS - Node Data Availability Sampling

Ethereum needs this proposal as the network aims to provide higher data availability for users, especially Rollup users.

However, in the current design of EIP-4844, each node still needs to download a large amount of blob data to verify whether it has been published. This creates a scalability issue because if all nodes must download all data, the network's bandwidth and hardware requirements will increase, impacting decentralization. To address this issue, Ethereum needs a method that allows nodes to confirm data availability without downloading all data.

Data Availability Sampling (DAS) solves this problem by allowing nodes to check only a small amount of random data.

However, Ethereum also needs a DAS method that is compatible with the existing Gossip network and does not impose a heavy computational burden on block producers. PeerDAS was created to meet these requirements and securely increase blob throughput while keeping node requirements low.

PeerDAS is a network system that allows nodes to download only small data segments to verify if complete data has been published. Nodes do not need to download all data but instead use a regular gossip network to share data, discover which nodes hold specific data parts, and request only the necessary small samples. The core idea is that by downloading only a small random part of a data segment, nodes can still be confident of the existence of the entire data segment. For example, a node may only download about 1/8 of the data rather than the full 256 KB data segment—but because many nodes sample different parts, any missing data is quickly discovered.

To enable sampling, PeerDAS uses a simple erasure code to expand each data segment in EIP-4844. Erasure coding is a technique that adds extra redundant data so that even if some data segments are missing, the original data can be recovered—similar to completing a jigsaw puzzle even if a few pieces are missing.

The blob becomes a "row" containing the original data and some additional encoding data to reconstruct the data later. Then, this row is divided into many small blocks called "cells," which are the smallest validation units associated with KZG commitments. All "rows" are then reorganized into "columns," where each column contains cells from the same position in all rows. Each column is assigned to a specific gossip subnet.

Nodes are responsible for storing certain columns based on their node ID and sampling some columns from peer nodes in each timeslot. If a node collects at least 50% of the columns, it can fully reconstruct the data. If it collects fewer than 50% of the columns, it requests the missing columns from peer nodes. This ensures that if the data has indeed been published, it can always be reconstructed. In short, if there are a total of 64 columns, a node only needs about 32 columns to reconstruct the entire blob. It retains some columns itself and downloads some columns from peer nodes. As long as half of the columns exist in the network, the node can rebuild all content, even if some columns are missing.

Furthermore, EIP-7594 also introduces an important rule: no transaction can contain more than 6 blobs. This limit must be enforced during transaction validation, gossip propagation, block creation, and block processing. This helps reduce the extreme case of a single transaction causing blob system overload.

PeerDAS has added a feature called "Unit KZG Proof." The Unit KZG Proof demonstrates that the KZG commitment indeed matches a specific cell in the blob (a small unit). This allows nodes to download only the cell they wish to sample. Ensuring data integrity while obtaining the full blob is crucial for data availability sampling.

However, the cost of generating all these unit proofs is high. Block producers need to repeatedly compute these proofs for many blobs, resulting in slow speeds. Nevertheless, the cost of proof verification is very low. Therefore, EIP-7594 requires blob transaction senders to pre-generate all unit proofs and include them in the transaction wrapper.

For this reason, transaction gossip (PooledTransactions) now uses a modified wrapper:

「rlp([tx_payload_body, wrapper_version, blobs, commitments, cell_proofs])」

In the new wrapper, cell_proofs is simply a list containing all proofs of each unit for each blob (e.g., [cell_proof_0, cell_proof_1, ...]). The other fields tx_payload_body, blobs, and commitments are identical to those in EIP-4844. The difference is that the original single "proofs" field has been removed and replaced with the new cell_proofs list, while a new field named wrapper_version has been added to indicate the current wrapper format in use.

PeerDAS enables Ethereum to improve data availability without increasing node workload. Today, a node only needs to sample approximately 1/8 of the total data. In the future, this ratio may even decrease to 1/16 or 1/32, thereby enhancing Ethereum's scalability. The system operates well because each node has numerous peer nodes; thus, if one peer node cannot provide the required data, the node can request it from other peer nodes. This naturally establishes a redundancy mechanism, enhances security, and allows nodes to choose to store data beyond the actual requirements, further strengthening network security.

A validating node bears more responsibility than a regular full node. Since validating nodes themselves run on more powerful hardware, PeerDAS assigns them a corresponding data hosting load based on the total number of validating nodes. This ensures that there is always a stable group of nodes available to store and share more data, thus enhancing the network's reliability. In short, if there are 900,000 validating nodes, each validating node may be assigned a small portion of the total data for storage and service. Because validating nodes have more powerful machines, the network can trust them to ensure data availability.

PeerDAS uses column sampling instead of row sampling because it significantly simplifies data reconstruction. If nodes sample the entire row (entire blob), it would require creating additional "extended blobs" that did not originally exist, slowing down the block producer's speed.

Through column sampling, nodes can prepare additional row data in advance, and the necessary proof is calculated by the transaction sender (not the block producer). This helps maintain the speed and efficiency of block creation. For example, suppose a blob is a 4x4 cell grid. Row sampling means taking all 4 cells from a row, but some extension rows are not ready, so the block producer has to generate them on the spot; column sampling involves extracting one cell from each row (each column), and the additional cells needed for reconstruction can be pre-prepared, allowing nodes to verify data without slowing down block generation speed.

EIP-7594 is fully compatible with EIP-4844, so it does not disrupt any existing features on Ethereum. All tests and detailed rules are included in the consensus and execution specifications.

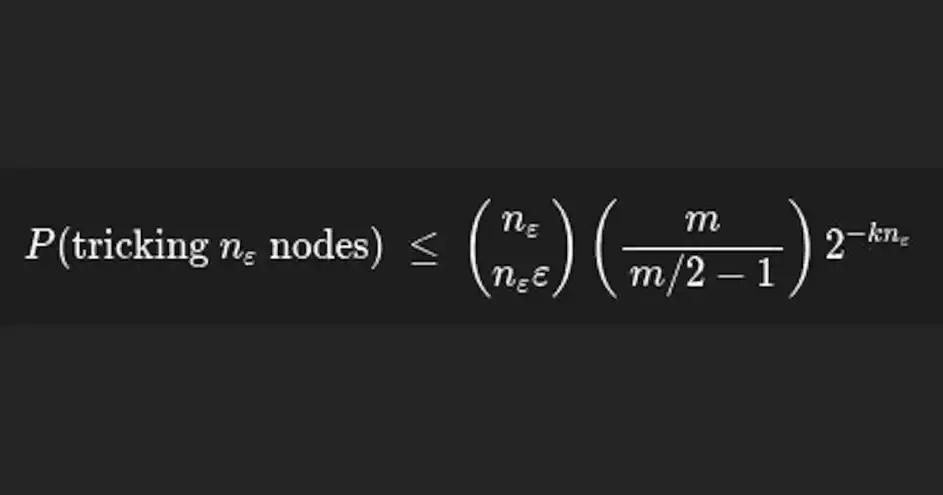

The primary security risk for any DAS system is "data withholding attacks," where block producers pretend that data is available but actually hide parts of the data. PeerDAS prevents this scenario by using random sampling: nodes check a random portion of the data. The more nodes sampled, the harder it is for attackers to cheat. EIP-7594 even provides a formula to calculate the likelihood of such an attack's success based on the total number of nodes (n), total samples (m), and samples per node (k). On the Ethereum mainnet with about 10,000 nodes, the probability of a successful attack is extremely low, making PeerDAS considered secure.

EIP-7823: Setting a 1024-Byte Limit for MODEXP

The necessity of this proposal arises from the fact that Ethereum's current MODEXP precompile mechanism has led to numerous consensus vulnerabilities over the years. These vulnerabilities mostly stem from MODEXP allowing an extremely large and impractical input data size, causing clients to deal with countless edge cases.

Due to the fact that each node must process all inputs provided by a transaction, the lack of an upper bound makes MODEXP more difficult to test, more prone to errors, and more likely to behave differently across different clients. The oversized input data also makes the gas cost formula hard to predict, as pricing becomes challenging when the data can grow infinitely. These issues also make it difficult to replace MODEXP with EVM-level code using future tools like EVMMAX, as developers cannot create a secure and optimized execution path without a fixed limit.

To mitigate these issues and improve Ethereum's stability, EIP-7823 introduced a strict upper limit on the MODEXP input data size, making the precompilation process more secure, testable, and predictable.

EIP-7823 introduces a simple rule: all three length fields used by MODEXP (base, exponent, and modulus) must be less than or equal to 8192 bits, i.e., 1024 bytes. MODEXP inputs follow the format defined in EIP-198: <len(BASE)> <len(EXPONENT)> <len(MODULUS)> <BASE> <EXPONENT> <MODULUS>, hence this EIP only constrains the length values. If any length exceeds 1024 bytes, the precompile will immediately halt, return an error, and consume all gas.

For instance, if someone attempts to provide a 2000-byte-long base, the call will fail before any work starts. These constraints still accommodate all practical use cases. RSA verification commonly employs key lengths of 1024, 2048, or 4096 bits, all of which fall within the new limit. Elliptic curve operations use smaller input sizes, typically less than 384 bits, and thus remain unaffected.

These new restrictions also facilitate future upgrades. Should EVMMAX be employed to rewrite MODEXP as EVM code in the future, developers can optimize pathways for common input sizes (e.g., 256 bits, 381 bits, or 2048 bits) and implement slower fallback options for rare scenarios. By fixing the maximum input size, developers can even introduce special handling for very common moduli. Previously, due to the unrestricted input size, the design space was overly vast and difficult to securely manage, rendering these efforts unfeasible.

To ensure that this change does not disrupt past transactions, the author analyzed all MODEXP usage from block 5,472,266 (April 20, 2018) to block 21,550,926 (January 4, 2025). The findings revealed that all historically successful MODEXP calls did not use inputs exceeding 513 bytes, well below the new 1024-byte limit. Most real-world calls utilized smaller lengths, such as 32 bytes, 128 bytes, or 256 bytes.

There are some invalid or corrupted invocations, such as empty inputs, inputs with repeated bytes, and a very large but invalid input. The behavior of these invocations under the new restriction is also invalid because they are inherently invalid. Therefore, while EIP-7823 is a significant technical change, in practice, it will not alter the outcome of any past transactions.

From a security standpoint, reducing the allowed input size does not introduce new risks. Instead, it eliminates unnecessary extreme scenarios that previously led to errors and inconsistencies between clients. By constraining MODEXP input to a reasonable size range, EIP-7823 makes the system more predictable, reduces odd edge cases, and lowers the probability of errors between different implementations. These restrictions also help prepare the system for future upgrades, such as EVMMAX, introducing optimized execution paths for a smoother transition.

EIP-7825: Transaction 16.7 Million Gas Limit

Ethereum does indeed need this proposal as currently a single transaction can nearly consume the entire block's Gas limit.

This poses several issues: a transaction may consume most of the block's resources, leading to slow delays akin to DoS attacks; gas-intensive operations rapidly escalate Ethereum's state updates; block validation slows down, making it difficult for nodes to keep pace.

If a user submits a transaction that consumes almost all the Gas in a block (e.g., a transaction consuming 38 million Gas in a 40 million Gas block), regular transactions cannot fit in that block, and each node must spend additional time to validate the block. This threatens the network's stability and decentralization as slower validation speed means weaker performance nodes fall behind. To address this issue, Ethereum needs a secure Gas limit, restricting the amount of Gas a single transaction can use to make block loads more predictable, reduce the risk of DoS attacks, and balance node loads.

EIP-7825 introduces a hard rule: no transaction shall consume more than 16,777,216 Gas (2²⁴). This becomes a protocol-level limit, meaning it applies to all stages: user transaction submission, transaction pool transaction checks, and validator block inclusion. If someone submits a Gas limit exceeding this value, the client must promptly reject the transaction and return an error similar to MAX_GAS_LIMIT_EXCEEDED.

This limit is completely independent from the block Gas limit. For example, even if the block Gas limit is 40 million, the Gas consumption of any single transaction must not exceed 16.7 million. The purpose is to ensure that each block can accommodate multiple transactions, rather than allowing a single transaction to occupy the entire block.

To better understand this, consider a block that can hold 40 million Gas. Without this limit, someone could send a transaction consuming 35 to 40 million Gas. This transaction would monopolize the block, leaving no room for other transactions, similar to someone taking up an entire bus, preventing others from boarding. The new 16.7 million Gas limit will naturally allow blocks to include multiple transactions, avoiding such abuse.

The proposal also sets specific requirements for how clients should validate transactions. If a transaction's Gas exceeds 16,777,216, the transaction pool must reject it, meaning such transactions will not even enter the queue. During block validation, if a block contains transactions above the limit, the block itself must be rejected.

The choice of 16,777,216 (2²⁴) as the number is because it is a clear power of 2 boundary, easy to implement, and still large enough to handle most real-world transactions. For example, smart contract deployment, complex DeFi interactions, or multi-step contract calls. This value is roughly half the typical block size, meaning even the most complex transactions can easily fit within this limit.

This EIP also maintains compatibility with the existing Gas mechanism. Most users will not notice this change because almost all existing transactions consume far less than 16 million. Validators and block creators can still create blocks with a total Gas exceeding 16.7 million, as long as each transaction complies with the new limit.

The only affected transactions are those that previously attempted to use oversized transactions that exceed the new limit. These transactions must now be split into multiple smaller operations, similar to breaking up a very large file upload into two smaller files. Technically, this change is not backward compatible for these rare extreme transactions, but the number of affected users is expected to be very small.

In terms of security, the Gas limit makes Ethereum more resistant to Gas-based DoS attacks, as attackers can no longer force validators to process oversized transactions. It also helps maintain predictability in block validation time, making it easier for nodes to stay synchronized. In extreme cases, a few very large-scale contract deployments may not meet the limit requirements and will need to be redesigned or split into multiple deployment steps.

Overall, EIP-7825 aims to strengthen network abuse prevention, keep node requirements reasonable, improve fairness in block space usage, and ensure that as the Gas limit increases, the blockchain can still maintain fast and stable operation.

EIP-7883: ModExp Gas Fee Increase

The reason Ethereum needs this proposal is that the price of the ModExp precompile (used for modular exponentiation) has always been lower compared to the resources it actually consumes.

In some cases, the amount of computation required for ModExp operations far exceeds the fee users currently pay. This mismatch poses a risk: if the price of complex ModExp calls is too low, they might become a bottleneck, making it difficult for the network to safely increase the Gas limit. This is because block producers may be forced to handle extremely heavy operations at very low cost.

To address this issue, Ethereum needs to adjust the pricing formula for ModExp to ensure that Gas consumption accurately reflects the actual work done by the client. Therefore, EIP-7883 introduces new rules that raise the minimum Gas cost, increase the total Gas cost, and make operations with larger input data (especially operations with exponents, bases, or moduli exceeding 32 bytes) more expensive, aligning Gas pricing with the actual computational effort required.

This proposal increases costs through several key aspects, thus modifying the ModExp pricing algorithm initially defined in EIP-2565.

Firstly, the minimum Gas consumption is raised from 200 to 500, and the total Gas consumed is no longer divided by 3, meaning the total Gas consumed is effectively tripled. For example, if a ModExp call previously required 1200 gas, it will now require approximately 3600 gas under the new formula.

Secondly, the cost of operations with exponents larger than 32 bytes doubles, as the multiplier goes from 8 to 16. For instance, if the exponent length is 40 bytes, EIP-2565 would increase the iteration count by 8 × (40 − 32) = 64, while EIP-7883 now uses 16 × (40 − 32) = 128, doubling the cost.

Thirdly, pricing now assumes a minimum base/modulus size of 32 bytes, and when these values exceed 32 bytes, the computation cost increases significantly. For example, if the modulus is 64 bytes, the new rule applies double complexity (2 × words²), as opposed to the simpler previous formula, reflecting the actual cost of large number operations. These changes collectively ensure that small ModExp operations pay a reasonable minimum fee, and the cost of large, complex operations adjusts appropriately based on their size.

This proposal defines a new Gas cost function, updating the complexity and iteration count rules. The multiplication complexity now uses a default value of 16 for base/modulus lengths not exceeding 32 bytes, and for larger inputs, it switches to the more complex formula of 2 × words², where "words" refers to the number of 8-byte blocks. The iteration count has also been updated, such that exponents of 32 bytes or smaller use their bit length to determine complexity, while exponents larger than 32 bytes incur a higher Gas penalty.

This ensures that extremely costly computations for very large exponents now have a higher Gas cost. Importantly, the minimum returned Gas cost has been mandated to be 500, instead of the previous 200, making even the simplest ModExp call more reasonable.

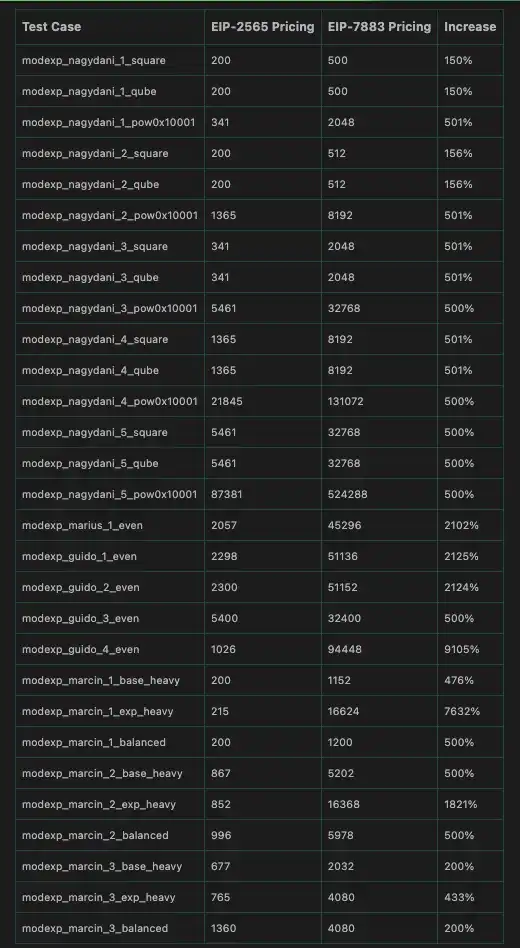

The motivation for these price hikes stems from benchmarking tests that revealed the pricing of the ModExp precompile to be significantly low in many cases. The revised formula raises the Gas cost of small operations by 150%, typical operations by approximately 200%, and the Gas cost of large or unbalanced operations by a much higher factor, sometimes exceeding 80 times, depending on the size of the exponent, base, or modulus.

The purpose of this action is not to alter how ModExp works but to ensure that even in the most resource-intensive extreme scenarios, it does not threaten network stability or impede future increases in the block Gas limit. As EIP-7883 changes the amount of Gas required for ModExp, it is not backward compatible, but Gas repricing has occurred several times in Ethereum and has been well understood.

Test results indicate that the increase in Gas costs is quite significant. Approximately 99.69% of historical ModExp calls now either require 500 Gas (previously 200 Gas) or three times the previous price. However, certain high-load test cases see a larger increase in Gas costs. For instance, in an "exponentiation-heavy" test, Gas consumption surged from 215 to 16,624, an increase of about 76 times, because pricing for extremely large exponents is now more reasonable.

In terms of security, this proposal does not introduce new attack vectors or lower the cost of any operation. Instead, it focuses on mitigating a significant risk: underpriced ModExp operations that could allow an attacker to fill blocks with extremely heavy computations at very low cost. The only potential downside is that prices for some ModExp operations may be too high, but this is much preferable to the current issue of underpricing. The proposal does not introduce any interface changes or new features, so existing arithmetic behaviors and test vectors remain valid.

EIP-7917: Accurately Predicting the Next Proposer

Ethereum needs this proposal because the network's next epoch proposer schedule cannot be fully predicted. Even with the RANDAO seed for epoch N+1 known at epoch N, the actual proposer list may still change due to updates in the effective balance (EB) within epoch N.

These EB changes can come from penalties, slashing, rewards greater than 1 ETH, validator churn, or new deposits, especially after EIP-7251 increased the maximum effective balance to over 32 ETH. This uncertainty poses problems for systems that rely on knowing the next proposer in advance (e.g., precommitment-based protocols), which require a stable and predictable timetable to function smoothly. Validators may even attempt to "game" or manipulate their effective balance to influence the next epoch's proposer.

Due to these issues, Ethereum needs a way to make the proposer schedule fully deterministic for several upcoming epochs, ensuring it does not change due to last-minute EB updates and is easily accessible to the application layer.

To achieve this, EIP-7917 introduces a deterministic proposer lookahead mechanism, which precomputes and stores the proposer schedule for the next MIN_SEED_LOOKAHEAD + 1 epochs at the beginning of each epoch. In simple terms, the beacon state now includes a list called `proposer_lookahead`, which always covers the proposers for two full cycles (a total of 64 slots).

For example, when epoch N begins, this list already contains the proposers for each slot in both epoch N and epoch N+1. Then, as the network transitions into epoch N+1, the list shifts forward: removing proposer entries from epoch N, moving the entries from epoch N+1 to the front of the list, and adding new proposer entries for epoch N+2 to the end of the list. This makes the schedule fixed, predictable, and accessible for clients to read directly without recalculating proposers for each slot.

To keep it updated, the list moves forward at each epoch boundary: removing data from the previous epoch and calculating a new set of proposer indices for the next future epoch, adding them to the list. This process uses the same seed and effective balance rules as before but now calculates the schedule earlier, avoiding the impact of post-seed effective balance changes. The first block after a fork will also fill the entire lookahead range to ensure all future epochs have their schedule correctly initialized.

Assuming each epoch has 8 slots instead of 32 (for simplicity). Without this EIP, during the 5th epoch, even though you know the seed for the 6th epoch, if a validator is slashed or gains enough rewards to change their effective balance during the 5th epoch, the actual proposer for slot 2 of the 6th epoch could still change. With EIP-7917, Ethereum will precompute all proposers for the 5th, 6th, and 7th epochs at the start of the 5th epoch and store them sequentially in `prosopers_lookahead`. So even if balances change late in the 5th epoch, the proposer list for the 6th epoch remains fixed and predictable.

EIP-7917 fixes a longstanding flaw in the beacon chain design. It ensures that once the RANDAO from a previous epoch is available, the validator selection for future epochs cannot be altered. It also prevents "balance fluffing," where validators attempt to adjust their balances upon seeing the RANDAO to influence the next epoch's proposer list. The deterministic lookahead mechanism eliminates the entire attack vector, greatly simplifying security analysis. It also allows consensus clients to know in advance who will propose upcoming blocks, aiding in implementation and enabling application layers to easily validate proposer schedules through a Merkle proof of the beacon root.

Prior to this proposal, clients only computed the proposer for the current slot. With EIP-7917, they now compute the proposer list for all slots of the next epoch at once during each epoch transition. This adds a minor amount of work, but calculating proposer indices is very lightweight, mainly involving sampling the validator list using a seed. However, clients will need to benchmark to ensure this additional computation does not cause performance issues.

EIP-7918: Blob Base Fee Constrained by Execution Cost

Ethereum needs this proposal because the current Blob fee system (derived from EIP-4844) breaks down when Gas becomes the primary cost of Rollup execution.

Currently, most Rollups pay execution Gas (the cost of including Blob transactions in a block) far above the actual Blob fee. This poses a problem: even as Ethereum continuously lowers the Blob base fee, the total cost of Rollup does not actually change because the most costly part is still execution Gas. As a result, the Blob base fee will keep decreasing until it reaches the absolute minimum value (1 wei), at which point the protocol will no longer be able to use the Blob fee to control demand. Then, when Blob usage suddenly spikes, it will take many blocks for the Blob fee to recover to normal levels. This creates price instability and makes it difficult for users to predict.

For example, suppose a Rollup wants to publish its data: it needs to pay around 25,000,000 gwei for execution Gas (about 1,000,000 gas requiring 25 gwei), while the Blob cost is only about 200 gwei. This means the total cost is approximately 25,000,200 gwei, with almost all of the cost coming from execution Gas rather than Blob cost. If Ethereum continues to lower the Blob cost, for example, from 200 gwei to 50 gwei, then to 10 gwei, and eventually to 1 gwei, the total cost would hardly change and would still remain at 25,000,000 gwei.

EIP-7918 addresses this issue by introducing a minimum "reserve price" based on the execution base fee, preventing the Blob price from being too low and making the Blob pricing of Rollup more stable and predictable.

The core idea of EIP-7918 is simple: the price of Blob should never be lower than a certain amount of execution Gas cost (referred to as BLOB_BASE_COST). The value of calc_excess_blob_gas() is set to 2¹³, and this mechanism is achieved by making minor modifications to the calc_excess_blob_gas() function.

Typically, the function would adjust the base Blob fee based on whether the blob gas used in the block is above or below the target value. Under this proposal, if the Blob becomes "too low" relative to the execution Gas, the function will stop deducting the target blob gas. This accelerates the growth of excess blob gas, preventing further decreases in Blob base cost. Therefore, the Blob base cost now has a minimum value equal to BLOB_BASE_COST × base_fee_per_gas ÷ GAS_PER_BLOB.

To understand why this is necessary, we can look at the demand for Blob. Rollup is concerned with the total cost it pays: the execution cost plus the blob cost. If the execution Gas cost is very high, for example, 20 gwei, then even if the Blob cost decreases from 2 gwei to 0.2 gwei, the total cost remains almost the same. This means that lowering the Blob base cost has almost no impact on demand. In economics, this is known as "fee inelasticity." It results in an almost vertical demand curve: reducing the price will not increase demand.

In this scenario, the Blob base fee mechanism would become blind, continuing to decrease the price even if there is no response in demand. This is why the Blob base fee often drops to 1 gwei. Then, when actual demand increases later on, the protocol needs nearly full blocks for an hour or more to raise the fee to a reasonable level. EIP-7918 addresses this issue by establishing a reserve price linked to Gas execution, ensuring that Blob fees remain meaningful even when execution costs dominate.

Another reason for adding this reserve price is that nodes need to do a lot of additional work to validate the KZG proof of Blob data. These proofs ensure that the data in the Blob matches its commitment. Under EIP-4844, nodes only needed to validate one proof for each Blob, which was low cost. However, in EIP-7918, nodes need to validate more proofs. This is all due to EIP-7594 (PeerDAS), where Blob is divided into many small blocks called cells, each with its own proof, significantly increasing the validation workload.

In the long run, EIP-7918 also helps prepare Ethereum for the future. With technological advancements, the cost of storing and sharing data will naturally decrease, and Ethereum is expected to allow more Blob data storage over time. As Blob capacity increases, Blob fees (measured in ETH) will naturally decrease. The proposal supports this as the reserve price is pegged to the execution Gas price rather than a fixed value, allowing it to adjust based on network growth.

As Blob space and execution block space expand, their price relationship will remain balanced. Only in very rare cases where Ethereum significantly increases Blob capacity without increasing execution Gas capacity, the reserve price may be too high. In this case, Blob fees could eventually be higher than necessary. However, Ethereum does not plan to scale this way—the Blob space and execution block space are expected to grow in sync. Therefore, the chosen value (BLOB_BASE_COST = 2¹³) is considered safe and balanced.

When the execution Gas fee suddenly spikes, one small detail needs to be understood. Since Blob's price depends on the execution base fee, a sudden increase in execution costs may temporarily put Blob fees in a state dominated by execution costs. For example, suppose the execution Gas fee suddenly jumps from 20 gwei to 60 gwei within one block. Because Blob's price is tied to that value, Blob fees cannot drop below the new, higher level. If Blobs are still being used, their fees will continue to rise as usual, but the protocol will not allow them to decrease until they have increased enough to match the higher execution costs. This means that for several blocks, the growth rate of Blob fees may be slower than the execution costs. This brief delay is harmless—it can actually prevent drastic fluctuations in Blob prices and make the system more stable.

The author also conducted an empirical analysis of actual on-chain transaction activity from November 2024 to March 2025, applying the reserve pricing rule. During high gas fee periods (averaging around 16 gwei), the reserve threshold significantly increased the block base fee compared to the old mechanism. During low gas fee periods (averaging around 1.3 gwei), the block fee remained almost unchanged unless the computed block base fee was below the reserve price. By comparing thousands of blocks, the author demonstrated that the new mechanism, while maintaining a natural response to demand, can also create a more stable pricing. A four-month block fee histogram shows that the reserve price prevents block fees from plummeting to 1 gwei, thereby reducing extreme volatility.

Regarding security, this change does not introduce any risk. The base block fee will always be equal to or higher than the execution gas BLOB_BASE_COST unit cost. This is secure because the mechanism only increases the minimum fee, and setting a price floor does not affect the protocol's correctness. It simply ensures a healthy economic operation.

EIP-7934: RLP Execution Block Size Limit

Prior to EIP-7934, Ethereum did not have a strict upper limit on the size of RLP-encoded execution blocks. Theoretically, if a block contained a large number of transactions or very complex data, its size could become very large. This led to two main issues: network instability and the risk of denial-of-service (DoS) attacks.

If a block is too large, it takes longer for nodes to download and validate, slowing down block propagation speed and increasing the likelihood of temporary blockchain forks. Even worse, an attacker could intentionally create a very large block to overload nodes, causing delays or even knocking them offline — a typical denial-of-service attack. Additionally, Ethereum's consensus-layer (CL) Gossip protocol already rejects propagating any block over 10MB, meaning excessively large execution blocks may fail to propagate in the network, leading to on-chain fragmentation or inter-node discrepancies. Given these risks, Ethereum needs a clear protocol-level rule to prevent oversized blocks and maintain network stability and security.

EIP-7934 addresses this issue by introducing a protocol-level limit on RLP-encoded execution block size. The allowed maximum block size (MAX_BLOCK_SIZE) is set to 10 MiB (10,485,760 bytes), but due to the beacon block's footprint (SAFETY_MARGIN), Ethereum adds an additional 2 MiB (2,097,152 bytes) on top of this.

This means the actual maximum allowed RLP encoded block size is MAX_RLP_BLOCK_SIZE = MAX_BLOCK_SIZE - SAFETY_MARGIN. If the encoded block is larger than this limit, the block will be considered invalid, and nodes must reject it. With this rule in place, block producers must check the encoding size of every block they construct, and validators must verify this limit during block validation. This size limit is independent of the Gas limit, meaning that even if a block is "under the Gas limit," it will still be rejected if its encoded size is too large. This ensures compliance with both Gas usage and actual byte size limits.

The choice of a 10 MiB limit is intentional as it aligns with existing limits in the consensus layer's gossip protocol. Any data larger than 10 MiB will not be broadcasted on the network, ensuring that the execution layer stays consistent with the consensus layer. This ensures consistency across all components and prevents valid execution blocks from being "invisible" due to CL refusing to propagate.

This change is not backwards compatible with blocks larger than the new limit, meaning miners and validators must update their clients to comply with this rule. However, since super large blocks themselves pose issues and are not common in actual operation, the impact is minimal.

In terms of security, EIP-7934 ensures that no participant can create a block that would cripple the network, significantly enhancing Ethereum's ability to withstand DoS attacks targeting specific block sizes. In summary, EIP-7934 establishes a critical security boundary, improves stability, aligns execution logic (EL) and CL behaviors, and prevents various attacks related to the creation and propagation of super large blocks.

EIP-7939: Leading Zero Count (CLZ) Opcode

Prior to this EIP, Ethereum did not have a built-in opcode to calculate the number of leading zeros in a 256-bit number. Developers had to manually implement the CLZ function in Solidity, which required numerous bitwise shifts and comparisons.

This posed a significant issue as custom implementations were slow, costly, and consumed a considerable amount of bytecode, thereby increasing Gas consumption. For zero-knowledge proof systems, the cost was even higher, as the proof cost of right shift operations is exorbitant. Thus, operations like CLZ significantly slowed down the execution of zero-knowledge proof circuits. Since CLZ is a highly common low-level function used in math libraries, compression algorithms, bitmaps, signature schemes, and many encryption or data processing tasks, Ethereum needed a faster, more cost-effective computation method.

EIP-7939 addressed this issue by introducing a new opcode called CLZ (0x1e). The opcode reads a 256-bit value from the stack and returns the number of leading zeros. If the input number is zero, the opcode returns 256, as a 256-bit zero has 256 leading zeros.

This aligns with how CLZ works on many CPU architectures like ARM and x86, where CLZ is natively supported. Adding CLZ can significantly reduce the overhead of many algorithms: lnWad, powWad, LambertW, various mathematical functions, byte string comparisons, bitmap scans, call data compression/decompression, and post-quantum signature schemes all benefit from faster leading zero detection.

The gas cost of CLZ is set to 5, similar to ADD, and slightly higher than the previous MUL price to avoid underpricing and the risk of Denial-of-Service (DoS) attacks. Benchmark tests show that the computational cost of CLZ is roughly the same as ADD and, in an SP1 rv32im proof-of-concept environment, the proof cost of CLZ is actually lower than that of ADD, thus reducing the cost of zero-knowledge proofs.

EIP-7939 is fully backward compatible as it introduces a new opcode without modifying any existing behavior.

Overall, EIP-7939 enhances Ethereum's performance by adding a simple and efficient primitive supported by modern CPUs, making Ethereum faster, more cost-effective, and more developer-friendly—reducing Gas fees, decreasing bytecode size, and lowering the cost of zero-knowledge proofs for many common operations.

EIP-7951: Support for Modern Hardware Signatures

Prior to this EIP, Ethereum lacked a secure, native way to validate digital signatures created using the secp256r1 (P-256) curve.

This curve is a standard used by modern devices such as Apple Secure Enclave, Android Keystore, HSMs, TEEs, and FIDO2/WebAuthn secure keys. Due to the absence of this support, applications and wallets could not easily leverage device-level hardware security for signing. There was a previous attempt (RIP-7212), but it had two critical security vulnerabilities related to point at infinity handling and incorrect signature comparisons. These issues could lead to verification failures and even consensus failures. EIP-7951 fixes these security issues and introduces a secure, native precompile, enabling Ethereum to securely and efficiently support signatures from modern hardware.

EIP-7951 added a new precompiled contract at address 0x100 named P256VERIFY, which performs ECDSA signature verification using the secp256r1 curve. Compared to implementing the algorithm directly in Solidity, this makes signature verification faster and more cost-effective.

EIP-7951 also defines strict input validation rules. If any invalid condition is present, the precompile will return failure without reverting, consuming the same amount of gas as a successful call. The verification algorithm follows the standard ECDSA: it computes s⁻¹ mod n, reconstructs the signature point R', rejects if R' is at infinity, and finally checks if the x-coordinate of R' matches r (mod n). This corrects the mistake in RIP-7212, where RIP-7212 directly compared r', instead of first reducing it modulo n.

The gas cost for this operation is set at 6900 gas, higher than the RIP-7212 version, but in line with the actual performance benchmarks for secp256r1 verification. Importantly, this interface is fully compatible with Layer 2 networks where RIP-7212 has been deployed (same address, same input/output format), so existing smart contracts will continue to function as usual without any changes. The only difference is the corrected behavior and the higher gas cost.

From a security perspective, EIP-7951 restores the correct behavior of ECDSA, eliminating malleability issues at the precompile level (leaving optional checks to applications), and explicitly stating that the precompile does not need to execute in constant time. The secp256r1 curve provides 128-bit security and has gained widespread trust and analysis, making it safe for use on Ethereum.

In summary, EIP-7951 aims to securely introduce identity verification supported by modern hardware to Ethereum, fix security issues in early proposals, and provide a reliable, standardized way to verify P-256 signatures across the entire ecosystem.

Summary

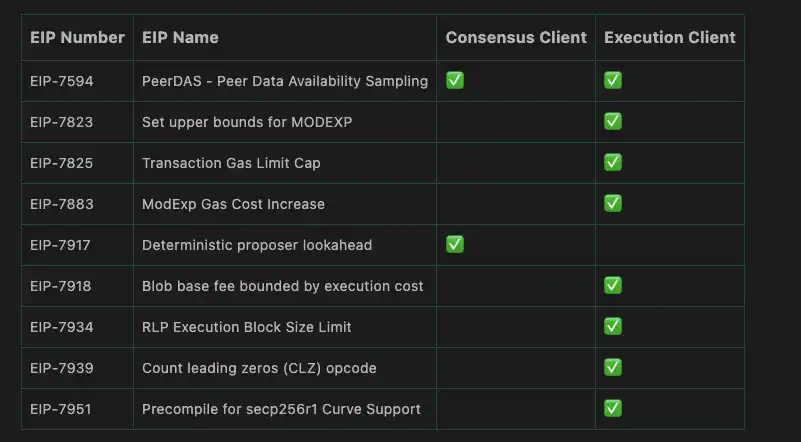

The table below summarizes which Ethereum clients need to be modified for different Fusaka EIPs. A checkmark under Consensus Client indicates that the EIP requires an update to the consensus layer client, while a checkmark under Execution Client indicates that the upgrade affects the execution layer client. Some EIPs require updates to both the consensus and execution layers, while others only need an update in one layer.

In conclusion, the above is the key EIP included in the Fusaka hard fork. While this upgrade involved multiple improvements to both consensus and execution clients, from Gas adjustments and opcode updates to new precompiles, the core of this upgrade is PeerDAS, which introduces peer-to-peer data availability sampling to enable more efficient and decentralized handling of Blob data across the entire network.

Welcome to join the official BlockBeats community:

Telegram Subscription Group: https://t.me/theblockbeats

Telegram Discussion Group: https://t.me/BlockBeats_App

Official Twitter Account: https://twitter.com/BlockBeatsAsia