a16z Raises $15 Billion in New Funds: Long Criticized, How Did It Become the "Best Storyteller" in Venture Capital?

Original Title: a16z: The Power Brokers

Original Source: Not Boring

Original Translation: Saoirse, Foresight News

Editor's Note: This article is written by Packy McCormick, the founder of Not Boring Capital and current a16z crypto advisor. The article focuses on the venture capital giant a16z, leveraging the opportunity of its newly raised $15 billion fund to dig deep into its "non-traditional venture capital" core — laying out the future with an engineer's mindset and betting on high-potential companies (such as Databricks) with unwavering conviction. The article intersperses performance data and classic cases, dissecting its advanced logic from startups to managing over $90 billion in assets. If you want to understand how this "tech believer" is reshaping industry rules, it's worth delving into the article.

When a16z announced the $15 billion new fund, the entire venture capital circle was once again stirred up — some questioning its model after many years, some curious about where this money will flow.

In order to understand this constantly controversial institution, I chatted with its GPs (General Partners) and LPs (Limited Partners), deep-dived with founders of post-investment companies valued at over $200 billion, and combed through its fund return data since its inception.

But rather than fussing over "where a16z went wrong," I am more interested in asking: What are those smart people who have always been able to make the right judgments in the past really aiming at now? Of course, I must admit, I was once an a16z crypto advisor, listed alongside key figures as a shareholder, so I am not a completely objective observer.

But I don't want to judge whether this $15 billion investment is worth it — institutional LPs have already voted with real money, and the answer will not be revealed until ten years later. I want to show you why a16z can become the "best storyteller" in the venture capital circle? What kind of unconventional ambition is hidden in its vision of the future?

"I live in the future, so the present is my past. My presence is a present, kiss my ass."

—Kanye West, "Monster"

"Too ostentatious," "Should speak less and do more in politics," "Don't agree with one or two recent investment projects," "Using the Pope's words to launch a social platform is inappropriate," "With a fund size so large, it's impossible to bring reasonable returns to LPs"...

These voices, a16z has been listening to for nearly 20 years.

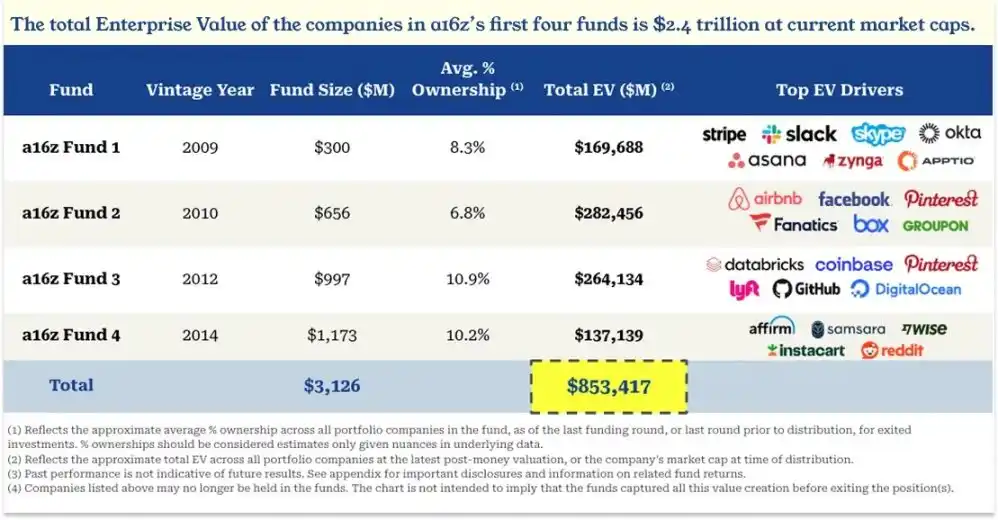

For example, in 2015, New Yorker writer Tad Friend, in his piece "Tomorrow's Advance Man," had breakfast with Marc Andreessen (co-founder and general partner at a16z). Prior to that, Friend had just heard skepticism from a peer VC: a16z's fund size was too large but its ownership percentage was too low [1], to achieve 5-10x total returns for the first four funds, the portfolio's total valuation would need to reach $240-480 billion.

Friend wrote in the article: "As I tried to fact-check these numbers with Andreessen, he made a dismissive gesture, saying, 'Nonsense. We have a full deck model—we are here to hunt elephants, go after whales!'

Remember this scene, as you may have similar doubts next, and Andreessen will most likely have the same reaction."

Today, a16z announces that all its investment strategies have raised a total of $15 billion, surpassing $90 billion in Regulatory Assets Under Management (RAUM).

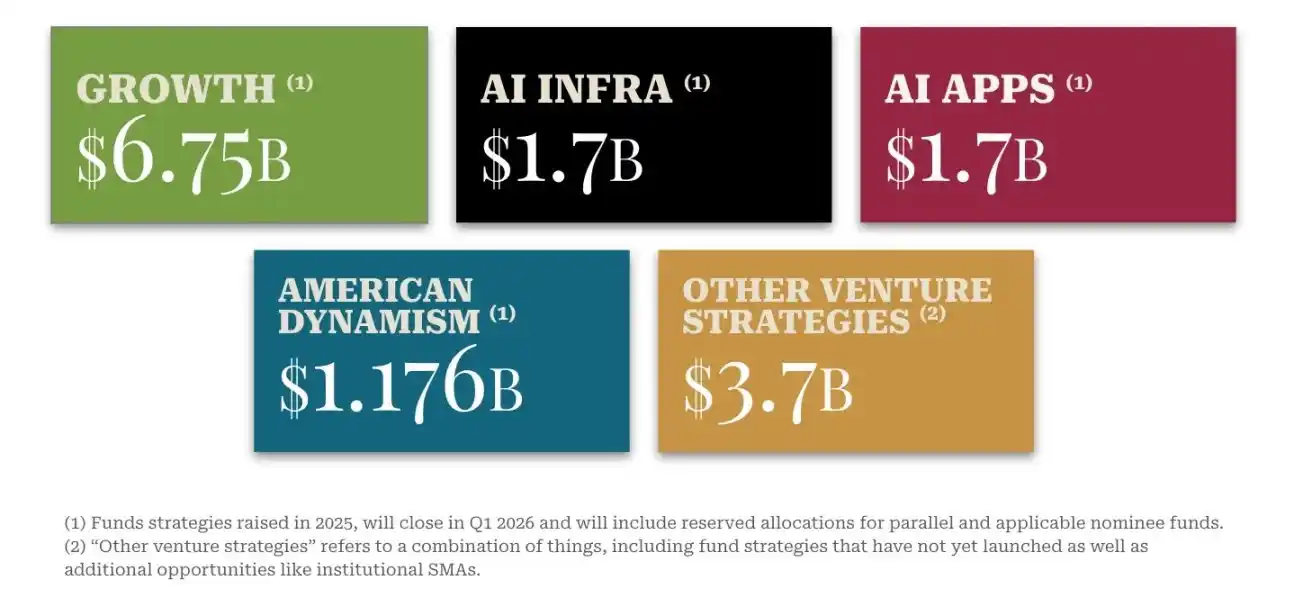

a16z Funds' Strategies and Corresponding Fund Sizes Raised in 2025

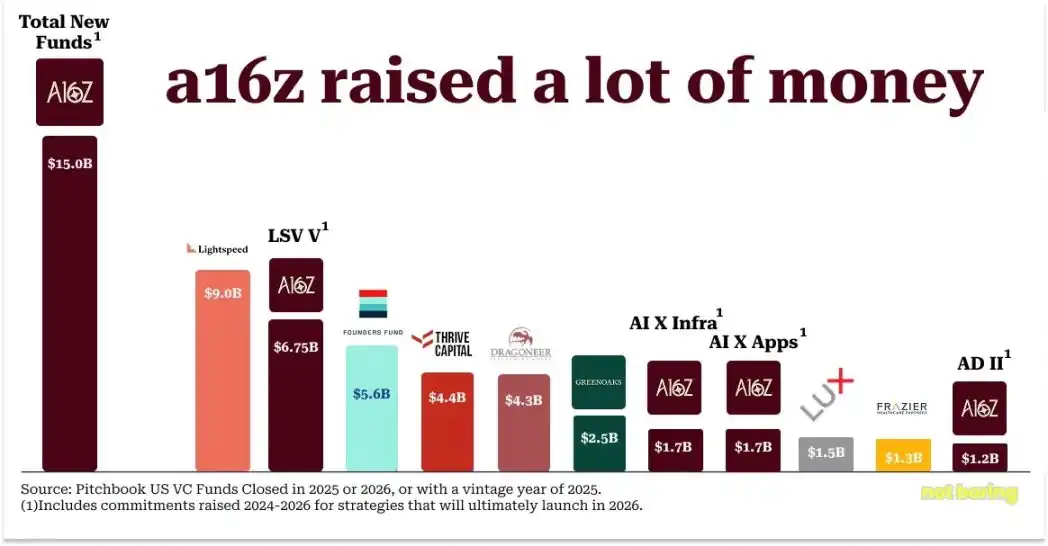

In 2025, the VC fundraising market was dominated by a few top institutions, and a16z's fundraising amount exceeded the combined total raised by second-ranked Lightspeed ($9 billion) and third-ranked Founders Fund ($5.6 billion) [2].

In the worst VC fundraising environment in nearly five years, a16z's 2025 fundraising amount accounted for over 18% of the total VC fundraising in the U.S. [3]. Typically, a VC fund takes an average of 16 months to complete fundraising, whereas a16z took just over three months from start to finish.

Breaking it down, a16z had four funds make it to the "Top 10 Fundraising in 2025 across all industries": Late-Stage Venture Fund LSV V ranked second, AI Infrastructure Fund X and AI Application Fund X tied for seventh, and the "U.S. Thrive Fund" AD II ranked tenth.

Comparison of Fundraising Scale of US Venture Capital Firms in 2025-2026

Some may say, with so much money, venture capital firms simply cannot allocate it sensibly to achieve outsized returns. But I guess a16z's response would probably be: "Nonsense." After all, they have always been about "Hunting Elephants, Chasing Whales"!

Today, among all of a16z's funds, its portfolio includes 10 of the "Top 15 Private Companies by Valuation": OpenAI, SpaceX, xAI, Databricks, Stripe, Revolut, Waymo, Wiz, SSI, and Anduril.

Over the past decade, a16z has invested in 56 unicorn companies through its funds, surpassing any other institution in the industry.

The total valuation of unicorn companies in its AI portfolio accounts for 44% of the entire industry [6], also ranking first.

From 2009 to 2025, a16z led early-stage rounds for 31 "eventually valued over $5 billion companies," 50% more than the sum of the second and third-ranked institutions.

They not only have a full set of models, but now they also have solid performance to back it up.

As mentioned earlier, peers once questioned whether the combined valuation of a16z's first four funds needed to reach $240-480 billion to meet the mark. The fact is, the total valuation of a16z's Funds I-IV (based on exit or latest post-money valuation) has already reached $853 billion [7].

Total Investment Portfolio Value of a16z's First Four Funds

And this is just the exit valuation—only Facebook alone added another $15 trillion to its market value later!

This kind of plot unfolds repeatedly: a16z makes a seemingly crazy bet on the future, industry insiders call it "stupid," but a few years later, they realize it wasn't stupid at all!

After the global financial crisis of 2009, a16z raised its $300 million Fund I and introduced the concept of "providing operational support platform for founders." Ben Horowitz (a16z's Co-Founder and General Partner) recalled: "We talked to many VC peers, most of them said it was a dumb idea, advised us not to do it, and even said this model had been tried before and simply wouldn't work." And today, almost all top VCs have similar platform teams.

In 2009, a16z pulled $65 million from this fund to join Silver Lake and other institutions in a $2.7 billion acquisition of Skype from eBay. At that time, "everyone said this deal wouldn't happen because the intellectual property risk was too great" — after all, during the transaction, eBay was in a legal battle with Skype's founders over the technology ownership. In less than two years, Microsoft acquired Skype for $8.5 billion, and Ben reminisced about the doubts in a blog post [8].

In September 2010, Marc and Ben raised a $650 million Fund II, then made large late-stage investments in companies like Facebook ($50 million, post-money valuation of $34 billion), Groupon ($40 million, post-money valuation of $5 billion), Twitter ($48 million, post-money valuation of $4 billion), betting that the IPO window was about to open. The Wall Street Journal wrote in an article titled "New Guard Rattles Silicon Valley" that their peers were quite displeased, believing that "trading equity in private deals was fundamentally not what venture capitalists should do" (at that time, this now common practice was still very new and not even called "secondary trading"). Benchmark Partner Matt Cohler once remarked, "You can make money trading pork bellies and oil futures, but that's not what we should be doing." The results? In November 2011, Groupon IPOed at a $17.8 billion valuation; in May 2012, Facebook IPOed at a $104 billion valuation; and in November 2013, Twitter closed its first day at a $31 billion valuation.

In January 2012, Marc and Ben raised a $1 billion Fund III, along with a $540 million parallel opportunity fund. The doubts at that time had turned into the now common "the fund is too large": a16z's fundraising amount that year accounted for 7.5% of the total U.S. venture capital fundraising, while the overall venture capital industry was underperforming. A 2014 Harvard Business School case study on a16z mentioned a report from the Kauffman Foundation in 2012 stating, "The venture industry has been terrible for over a decade." Cambridge Associates data showed that in 2012, the average venture capital return rate was only 8.9%, far below the S&P 500 index's 20.6%. Legendary venture capitalist Bill Draper once said, "The consensus in the Silicon Valley venture capital business is that too many funds are chasing too few really great companies." This statement still holds true today.

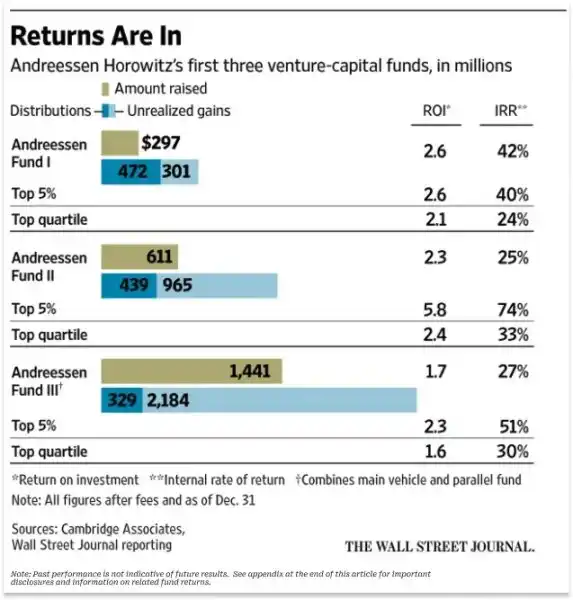

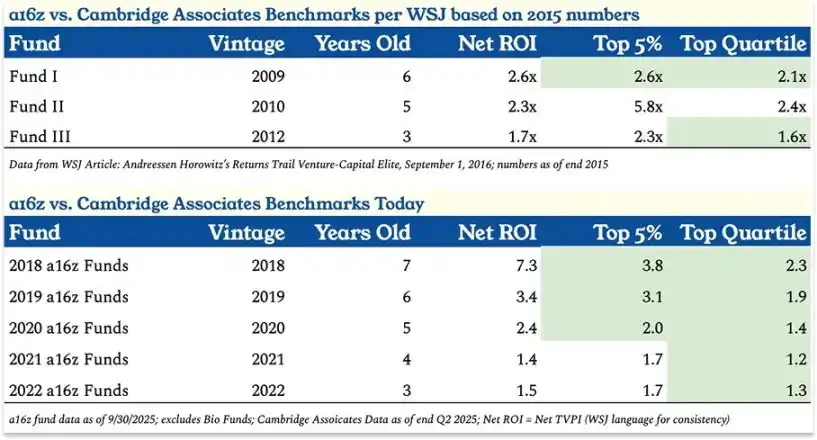

In 2016, The Wall Street Journal published an article where David Rosenthal of the Acquired podcast called it a "hit piece clearly sanctioned by rival VCs," titled "Andreessen Horowitz (a16z) Fund Lags Elite Venture Capital Returns." At that time, a16z's three funds were 7, 6, and 4 years old, with the article stating: Fund I could break into the top 5% of the industry, Fund II only in the top 25%, and Fund III didn't even make it to the top 25%.

Performance of a16z's Top 3 Funds and Comparison with Industry Leaders

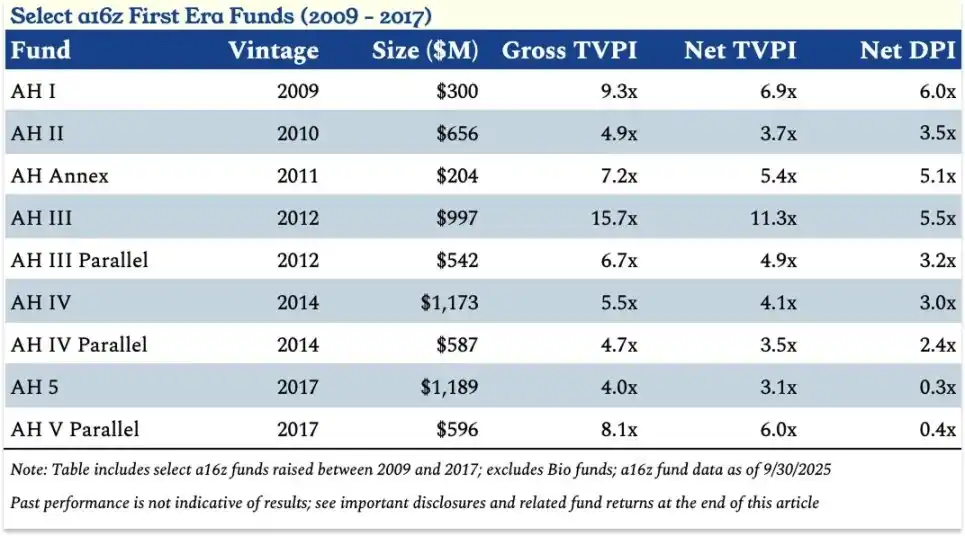

But in retrospect, this Fund 3 can be called a "legend": as of September 30, 2025, its net TVPI (Total Value to Paid-In capital) after fees reached 11.3x; including parallel funds, the net TVPI is 9.1x.

Fund 3's portfolio includes: Coinbase (bringing a total allocation of $7 billion to a16z LP), Databricks, Pinterest, GitHub, and Lyft (missed Uber, but a one-time omission "sin" ultimately cannot overshadow the "achievement" of multiple precise investments). I believe this fund can be called "one of the most successful large venture capital funds in history." By the end of Q3 2025, Databricks (currently a16z's largest position) has reached a valuation of $134 billion, indicating that Fund 3's performance is still rising (assuming other positions have not depreciated). From Fund 3 and parallel funds alone, a16z has already distributed a net $7 billion to LPs, with nearly an equivalent amount of unrealized gains yet to be realized.

A significant portion of these unrealized gains comes from Databricks. When the Wall Street Journal was pessimistic about a16z in 2016, this big data company was still small, a few months away from a valuation of $5 billion. Today, Databricks accounts for 23% of a16z's total Net Asset Value (NAV).

Anyone who has interacted with a16z will frequently hear the name "Databricks." Not only is it a16z's largest position (perhaps also one of the top three in terms of investment amount in the entire venture capital industry), its development path is a vivid example of a16z's "best operational model."

Databricks and a16z's Operational Formula

Before discussing Databricks, there are several key points about a16z that need to be understood.

First, a16z was founded and is run by engineers—not just founders, but "founder-engineers." This has influenced the institution's design logic (pursuing economies of scale and network effects) and also determines their standards for markets and companies.

Secondly, at a16z, being the "industry second" is perhaps the biggest "original sin of investing." If you miss out on the winner early on, you can still make a follow-on investment later; but if you invest in the second-place player, you will completely lose the opportunity to invest in the winner—even if the winner has not emerged yet.

Thirdly, once a16z identifies a company as a "category king," the classic move is to "invest far more money than the competition expects." This approach is often ridiculed in the industry, but they always stick to it.

These three points have never changed since the early days of a16z.

In the early 2010s, just a few years after a16z was founded, "big data" was the trend at the time, and the industry's mainstream big data framework was Hadoop. Hadoop adopted Google's MapReduce programming model, distributing computing tasks to a cluster of inexpensive commodity servers rather than expensive dedicated hardware, making it a promoter of "democratizing big data." Subsequently, a group of enterprises built around Hadoop emerged, and in 2014, the industry's investment fervor peaked: Cloudera, founded in 2008, raised $900 million, and the total funding for Hadoop-related companies that year increased fivefold compared to previous years, reaching $1.28 billion; Hortonworks, spun off from Yahoo, also held its IPO the same year.

While the big data trend was booming and funds were pouring in, a16z remained inactive.

The "z" in a16z—Ben Horowitz—simply did not believe in Hadoop. Prior to serving as the CEO of LoudCloud/OpsWare, with a background in computer science, he thought Hadoop would not become a mainstream architecture: "It's complex to program, difficult to manage, and not suited for future needs—every step of MapReduce computation must write intermediate results to disk, which is infuriatingly slow for iterative computing tasks like machine learning."

So Ben chose to steer clear of the Hadoop craze. Jen Kha told me that Marc even "complained" to Ben about this:

"'We definitely missed it! We messed up big time, made a major mistake!' Marc was extremely frustrated at the time.

But Ben said, 'I don't think this is the direction of the next architectural shift.'

Later, when Databricks emerged, Ben said, 'This might be it.' And then, of course, he went all in."

The birth of Databricks was timely and right near the University of California, Berkeley.

During the 1984 Iran Revolution, Ali Ghodsi's family fled Iran and relocated to Sweden. His parents bought Ali a Commodore 64 computer, and he taught himself programming on it. His skills were so advanced that he even received a visiting scholar invitation from the University of California, Berkeley.

In Berkeley, Ali joined the AMPLab research laboratory, where he, along with 8 researchers including mentors Scott Shenker and Ion Stoica, worked together to operationalize the ideas in PhD student Matei Zaharia's paper, developing Spark — an open-source big data processing engine.

The design philosophy behind Spark was "to replicate the functionality achieved by tech giants with neural networks without the need for complex interfaces." It once set a world record for data sorting speed, and Zaharia's paper was even awarded "Best Computer Science Paper of the Year." However, following the academic tradition, after they open-sourced the code, hardly anyone used it.

Starting in 2012, these 8 individuals had numerous dinner discussions and eventually decided to form a company around Spark, naming it Databricks. Seven of them became co-founders, with Shenker serving as an advisor.

Databricks co-founder Ali Ghodsi seated front and center, Forbes

The team initially thought they "needed some money, but not too much." Ben recalled in an interview with Lenny Rachitsky:

"When I met with them, they said, 'We need to raise $200,000.' And at that moment, I knew that they had Spark, and their competition was Hadoop companies with significant funding already. Besides, Spark was open source, and time was of the essence."

Ben also realized that as scholars, this team was "easily satisfied with small goals." He told Lenny, "Usually, if a professor's startup reaches a $50 million valuation, they are already a 'hero' on campus."

So, Ben delivered some "bad news" to the team: "I can't write a $200,000 check."

Next came the "good news": "I can write a $10 million check."

His reasoning was: "If you want to start a business, you have to take it seriously and go all in. Otherwise, you might as well stay in school."

The team decided to drop out. Ben further increased the investment, with a16z leading Databricks' Series A funding round, post-money valuation of $44 million, with a16z holding a 24.9% stake.

This initial encounter—Databricks asking for $200k, a16z investing $10 million—set the tone for the partnership: once a16z backs you, they will "completely believe in you" and push you to "aim for bigger goals."

When I asked Ali about the impact of a16z, his attitude was very clear: "I think if it weren't for a16z—especially Ben—Databricks wouldn't even exist today. I don't think we would have made it this far. They genuinely believed in us."

In the company's third year, revenue was only $1.5 million. "At that time, we had no idea if we would succeed," Ali recalled. "The only person who truly believed this company would be worth a fortune in the future was Ben Horowitz. His confidence was stronger than anyone else's, honestly, even stronger than my own. He deserves great credit for that."

Having faith is great, but its value becomes even greater when you have the ability to make that faith self-fulfilling.

For example, in 2016, Ali was trying to strike a deal with Microsoft. In his view, the market's demand to "integrate Databricks into the Azure cloud platform" was very urgent, and this partnership should have been a natural fit. He had asked a few VC partners to help facilitate introductions, hoping to get in touch with Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella—they did help, but those introductions ultimately "got lost in the executive assistant process and went nowhere."

Then, Ben personally intervened to establish a formal communication channel between Ali and Satya. "I received an email from Satya saying, 'We are very interested in establishing a deep partnership,'" Ali recalled. "He also cc'd his deputy and the deputy's subordinates. Within a few hours, my inbox was flooded with 20 emails, all from Microsoft employees I had previously tried to contact with no success, all asking in the emails, 'When can we meet to discuss further?' That's when I realized: 'Things are different now, this collaboration will definitely happen.'

For example, in 2017, Ali was trying to recruit a senior sales executive to drive the company's accelerated growth. This executive proposed adding a "change of control provision" to the contract — essentially, if the company were to be acquired, his shares would vest more quickly.

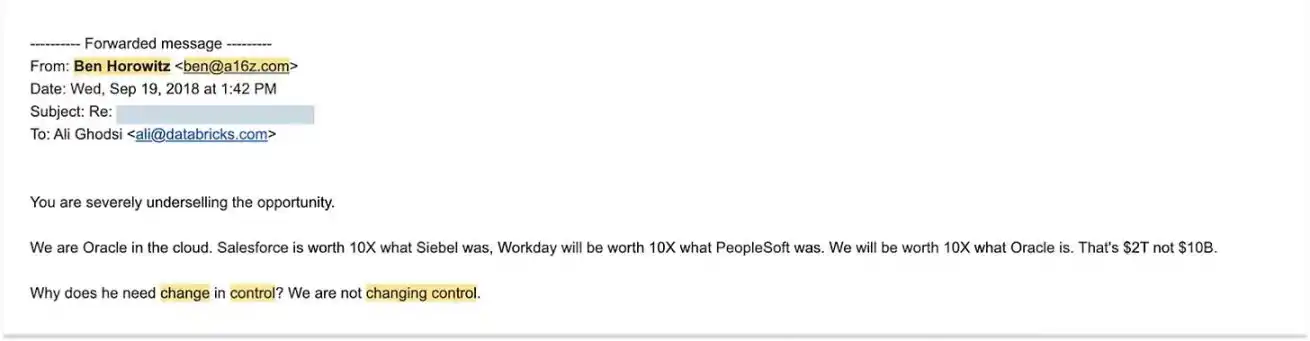

This became a sticking point in the negotiations, so Ali asked Ben to help convince this executive that he believed Databricks' valuation could "at least reach $10 billion." After Ben communicated with this executive, he sent Ali the following email:

Email from Ben Horowitz to Ali Ghodsi, September 19, 2018, provided by Ali Ghodsi

"You are significantly undervaluing this opportunity.

We will become the Oracle of cloud computing. Salesforce's valuation is 10 times Siebel's, Workday's valuation will be 10 times PeopleSoft's, and our valuation will be 10 times Oracle's — this means our target is $2 trillion, not $10 billion.

Why does he need a 'change of control provision'? We will not experience a change of control."

This is perhaps one of the most emphatic corporate emails in history, especially considering that at the time Databricks' revenue run rate (annualized revenue) was $100 million, with a valuation of only $10 billion; whereas today, the company's revenue run rate has exceeded $480 million, and the valuation has reached $134 billion.

"They could see the full potential of something," Ali told me. "When you're in it, dealing with day-to-day operations every day, facing various challenges — deals not closing, competition pressuring you, running out of funds, nobody knowing your company, employees leaving constantly — it's hard to take such a long-term view of the issues. But they would show up at board meetings and tell you, 'You will eventually conquer the world.'"

Their judgment was correct, and this belief brought them rich rewards. In conclusion, a16z participated in all 12 rounds of Databricks' financing, with 4 rounds led by a16z. It was because of investment targets like Databricks that a16z's initial investment in the AH 3 fund performed so well; at the same time, Databricks was also a key driver of return growth for the larger "Late Stage VC funds 1, 2, 4."

“First and foremost, they really care about the company's mission,” Ali remarked. “I don't think Ben and Marc see this primarily as a return-chasing investment; the investment return is secondary. They are true believers in technology, hoping to change the world with technology.”

If you can't understand Ali's assessment of Marc and Ben, you will never truly understand a16z.

What Exactly is a16z?

a16z is not a traditional venture capital fund. At first glance, this is evident: the company's latest fundraising is the largest in its entire strategy coverage since SoftBank's $98 billion Vision Fund in 2017 and Vision Fund II in 2019. This completely defies the characteristics of traditional VC. But even so, SoftBank's Vision Fund fundamentally remains just a "fund," while a16z is not.

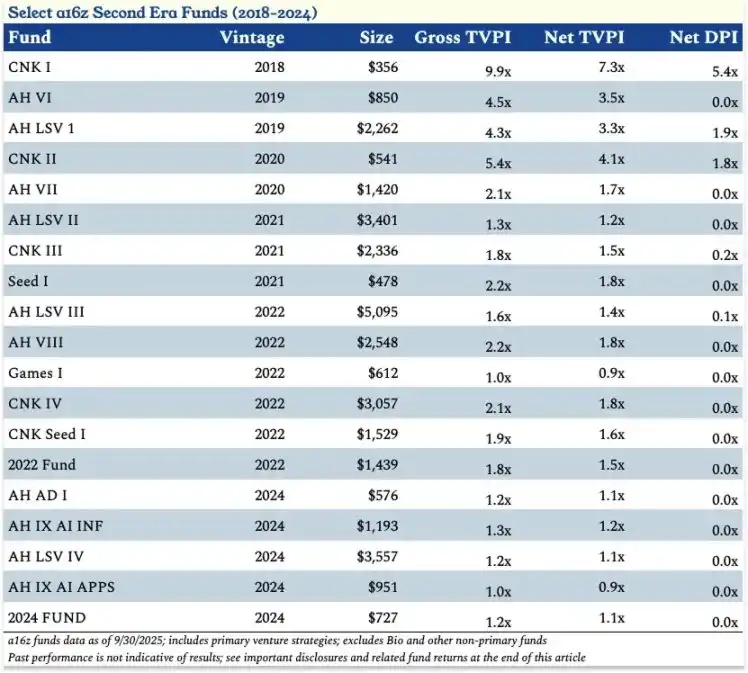

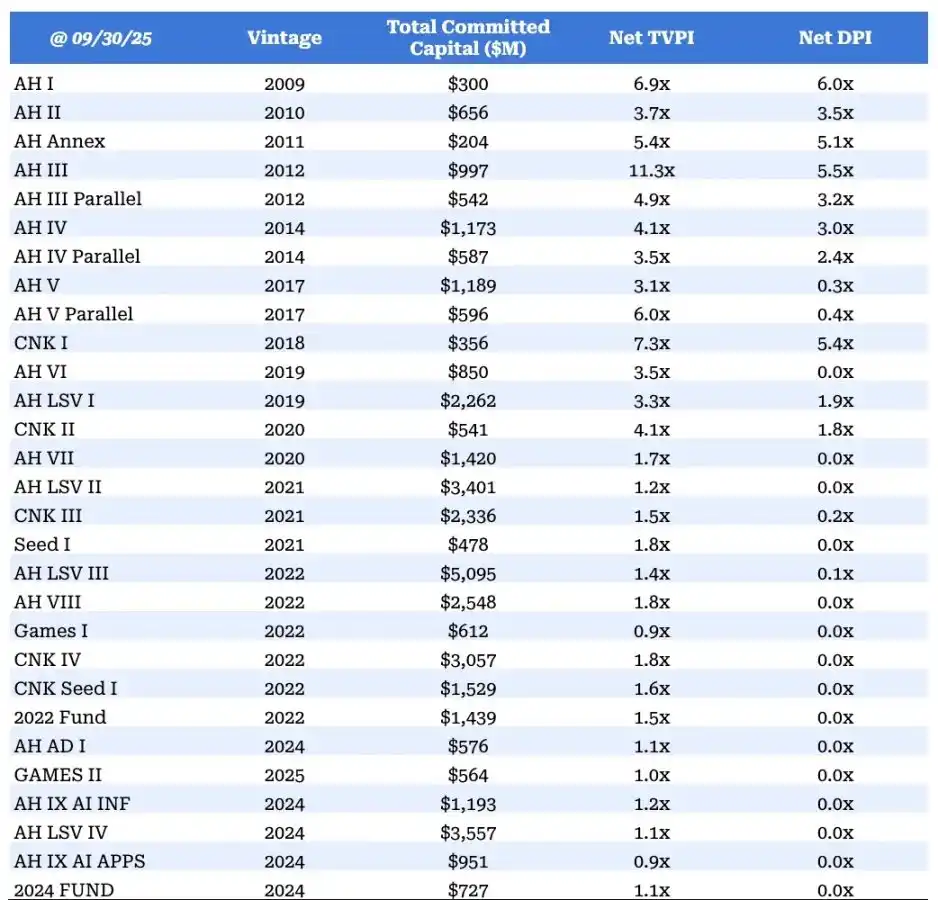

Of course, a16z has raised funds and needs to create returns for its investors. It must excel in this aspect, and so far, its performance has been outstanding. Not Boring has obtained the return data for a16z's funds to date, which we will share below.

But first, we need to be clear: What is a16z really?

a16z is a "tech-belief community." Everything it does is to drive the emergence of more advanced technology to create a better future. The company firmly believes: "Technology is the glory of human ambition and achievement, the vanguard of progress, the realization of human potential." All actions stem from this core belief. It holds a strong conviction about the future and places this belief at the stake of the entire company's resources.

a16z is an "institution." It is a business, a company built to achieve scalable growth and continuously improve itself in the process of scaling. I believe that an "institution" possesses many traits that a traditional "fund" does not have, which will be explained below. I think that positioning an "institution> fund" perfectly unravels the most contradictory aspect of self-awareness in the venture capital industry: providing the most scalable product (funds) to the most scalable potential enterprises (tech startups) while being considered as an industry that "should not scale."

This "institution> fund" distinction arises from a16z's General Partner (GP) David Haber. He is the team's most "Wall Street" individual and describes himself as a "student of investment institution business models." He explains: "The fund's objective function (core goal) is to earn the most significant side returns with the least manpower in the shortest time possible; whereas, the institution's goal is to create outstanding returns while building a competitive advantage that generates compounding effects. What we should be thinking about is: How do we make the company stronger, not weaker, in the scaling process?"

a16z is run by engineers and entrepreneurs. The typical approach of a traditional asset management firm is to compete for a larger share of a fixed “cake”; whereas engineers and entrepreneurs will make the “cake” itself larger by building a more robust system and driving system-level scale.

a16z is a “time-domain powerhouse,” an “institution built for the future.” In moments of grander ambition, this institution sees itself on par with the world’s top financial institutions and national governments. It has stated its goal is to become the “(first-gen) JPMorgan of the information age,” but in my view, this description still underestimates its true ambitions. If governments serve a “specific spatial realm,” then a16z serves the “broad time dimension of the future.” Venture capital is just one way it has found—through which it can have the greatest impact on the future, aligning with a logic of profiting by driving the future forward.

a16z creates and “sells” influence. It builds its own influence through scaled development, cultural construction, networks, organizational architecture, and past successes; it then bestows this influence upon the tech startups in its portfolio—primarily through support in sales, marketing, talent recruitment, government relations, and more. However, as put by its founders, a16z will “help in every way it can,” and it seems it can do far more than just that.

If you were to design such an institution—one that believes “technology is permeating markets far beyond traditional tech industry boundaries,” that “everything will eventually be tech-driven”—what you would ultimately create is a company that sells “capabilities to win,” targeting thousands of companies that could be at the core of the future economy. And I believe the institution you would end up creating would bear a striking resemblance to a16z.

Because those companies that could be at the core of the future economy are often small in scale and weak in foundation at the outset. They start off dispersed across various fields, each with different goals and competitors, often even competing with each other; meanwhile, they must face the giants dominating current markets, unwilling to yield to new entrants. A startup, not matter how promising, may struggle to attract top recruiters (thus failing to draw the best engineers and executives); may fail to advocate for policies that create a fair competitive environment; may lack a sufficient audience to have its ideas heard; may lack the necessary credibility to sell its products to government departments and large enterprises inundated with sales pitches promising to bring the next big thing.

For any single startup, investing billions to build the above capabilities, only to serve itself, is illogical; but if these capabilities can be spread across “all these startups,” covering a “future market value in the trillions,” then these small companies suddenly have the resources of larger companies. Their success will then depend solely on the quality of their products, and they can rightfully drive the future forward.

What would be the result of combining the agility and innovation of a startup with the influence and power of a "time domain master"?

This is exactly what a16z has been striving to do — starting from when it was a startup itself.

Why Did Marc and Ben Found a16z?

In June 2007, Marc wrote a blog post titled "The Only Thing That Matters," [11] which was part of the "Pmarca Guide to Startups" [12]. At first glance, this post offered advice to tech startups, but looking back now, it reads more like an "operations manual for starting a16z." The core of the post answered a question: among the three core elements of a startup — team, product, and market — which is the most important?

Entrepreneurs and venture capitalists often say "the team is most important;" engineers usually say "the product is most important."

"I, personally, subscribe to the third theory," Marc wrote, "I believe that the market is the most important factor determining the success or failure of a startup."

Why? He explained in the post:

"In a great market — a market with lots of real potential customers — the market pulls product out of the startup...

Conversely, in a lousy market, even with the best product in the world, the best team, you're going to fail...

In honor of Benchmark Capital's former partner Andy Rachleff, I hereby present 'The Rachleff Rule for Startups' :

The #1 company-killer is lack of market.

Andy says:

Good team, bad market = market wins;

Good market, bad team = market wins;

Good team, good market = magic happens."

I believe that what Marc and Ben saw in the venture capital industry was a "great market" (though no one realized how great it was at the time), filled with "bad teams" (again, no one realized how bad they were).

Between 2007 and 2009, Ben and Marc had been contemplating their next move. They were already very successful tech entrepreneurs—despite their success, they were still itching for more; and it was precisely because of this success that they had the capital to "not have to kiss ass" and could afford to take risks without any hesitation.

But what specifically to do?

Whether as entrepreneurs or later as angel investors, Marc and Ben had dealt with many unprofessional venture capitalists, and they felt that "competing with these people might be fun."

"To me, Marc doing this was never about the money," David Haber told me. "He was already very wealthy by the time he was around 20 years old. Initially, he probably did this more to 'show Benchmark or Sequoia a bit of color.'"

The venture capital industry had another quirk at a time when the global financial crisis (GFC) triggered the most severe economic downturn: hardly anyone realized this—it might be the best market in the world. And for Marc, this was crucial.

Of course, not all venture capital firms were terrible. The two companies Marc wanted to "show some color to"—Sequoia and Benchmark—were actually very excellent (Marc even quoted Andy Rachleff's perspective!), but they tended to have a "founder replacement" bias. And for founders who wanted to retain control, Peter Thiel had founded Founders Fund as early as 2005, which was in the investment period of "2007 Vintage Fund II" at that time. As Mario wrote, this fund eventually achieved a performance of "an 18.60x DPI."

But compared to today, the venture capital industry at that time was still a "reluctant, closed, labor-intensive industry."

Marc often tells a story: In 2009, when he and Ben were considering starting a16z, they met with a GP from a top venture capital firm, who likened investing in startups to "picking sushi off a conveyor belt." According to Marc's recollection, this GP said to him:

"Venture capital is like eating at a conveyor belt sushi restaurant. You just sit on Sand Hill Road, and startups will naturally come to you. Even if you miss one, it's okay because the next sushi will come around quickly. You just sit there, watch the 'sushi' go by, and occasionally reach out to grab one."

In the Uncapped podcast, Marc explained to Jack Altman, "If the goal is just to 'keep the good times going,' as long as the industry's ambition is limited, this approach is feasible."

But Marc and Ben's ambitions go far beyond that. In the company they are about to found, "missing out on a high-quality project"—that is, not being able to invest in an outstanding company—would be the biggest mistake. This is no small matter because they clearly see: as the market size expands, the scale of those large tech companies will become unimaginably large.

"Ten years ago, there were about 50 million Internet users, even fewer with broadband connections," Ben and Marc wrote in the April 2009 memorandum for the "a16z Fund I," "Today, there are about 1.5 billion Internet users, many of whom have broadband connections. Therefore, whether on the consumer side or the infrastructure side, the most successful companies in the industry may have far greater potential than the most successful tech companies of the previous generation."

At the same time, the cost of starting a company has significantly decreased, and processes have become simpler—meaning that there will be more startups in the future.

In a letter to potential limited partners (LPs), they wrote, "Over the past decade, the cost of developing a new technology product and bringing it to market at least in beta form has dropped significantly; today, this cost is usually only $0.5 to $1.5 million, compared to $5 to $15 million a decade ago."

Finally, as startups transition from being "tool providers" to "players directly competing with industry giants," their own ambitions are also constantly expanding—meaning that all industries will eventually become tech industries, and the scale of all industries will therefore become larger.

This is why at that particular juncture, the "market" was so prime. Marc then continued:

"From the 1960s to around 2010, the venture capital industry had a fixed 'script'... The companies at that time were essentially 'tool providers,' that is, 'companies selling picks and shovels'—mainframes, desktop computers, smartphones, laptops, internet access software, SaaS (Software as a Service), databases, routers, switches, disk drives, word processing software, all of these were tools.

Around 2010, the industry underwent a permanent transformation... The most successful companies in the tech sector are increasingly those that directly enter traditional industries and compete with existing giants."

In the early days, was a16z guilty of "overpricing" companies? Or was the pricing actually reasonable relative to the future potential they foresaw in these companies?

Looking back now, it's easy to argue the latter; but what's impressive about a16z is that they held this view even before events unfolded.

As they wrote in their post: about 15 tech companies each year eventually hit $1 billion in annual revenues, and these companies, in total market value created, represent 97% of all market value created that year across all companies—this is the well-known "Power Law." And so, they had to do whatever it took to invest as much as possible in companies "that had the potential to be one of those 15"; then, within those companies, double down and triple down on the winners.

And to execute on that, it wasn’t enough to have just two investing partners—a16z had to construct the firm in a way that was "fundamentally different from every other peer."

So, after outlining the basic terms of the "AH Fund I" (which targeted to raise $2.5 billion with LPs committing $15 million each), Ben and Marc summarized the core strategy of the firm in a sentence.

AH Fund I Memo

Even as the firm has grown far beyond "two partners" and its ambitions are no longer bounded by simply "getting into the top five," they continue executing on this strategy to this day.

a16z's Three Phases of Development

Since the inception of their first fund, looking at the entirety of the firm's arc, I see a16z's extraordinary belief in the future, its asymmetric conviction, as its enduring core competitive advantage. It is this differentiating trait that spawns all other competitive advantages.

As the firm's ambition, resources, fund sizes, and influence have grown, the ways in which they apply this advantage and achieve differentiation have evolved.

Phase One (2009 - Circa 2017)

In a16z's Phase One (2009 - Circa 2017), the core insight was: if "software is eating the world," then the value of top software companies would vastly exceed everyone's valuation expectations at the time.

With this belief, a16z took three actions and successfully went from being a newcomer to a top 5 investment firm in the industry:

Placing High-Bid Orders: As mentioned earlier, some of the early deals made by a16z's funds were seen by many peers at the time as overpriced or deviating from the usual track. In the "Acquired" podcast, Ben Gilbert stated, "Critics widely criticized them for 'spending money to buy reputation,' squeezing into high-quality projects through high-priced investments," but at the same time, he pointed out that this approach was reasonable at the time and asked, "Would anyone still think that any project a16z invested in between 2009 and 2015 was actually valued too high? The answer is definitely no." As explained by Ben Horowitz in a 2014 Harvard Business School (HBS) case study, "Even in the face of multi-billion-dollar valuations, investors may still underestimate the potential of these companies." And this "underestimation" is exactly where a16z found its opportunity.

Building Operation Infrastructure Others Deemed as "Waste": Establishing a full-service team, hiring recruiting partners, setting up an executive briefing center... To fund managers at the time, these initiatives seemed like "additional expenses" that would drag down costs. But if one believes that the companies in the portfolio can grow to become the industry benchmarks of a "category-defining" nature and need enterprise-level strength to achieve this goal, then these investments are justified. a16z's move was a strategic setup for the future—where startups must present an "enterprise-like" image in the future to win cooperation orders from Fortune 500 companies.

Viewing Technical Founders as a Scarce Resource: This was also a gamble—due to the reduced cost of founding a company and the lower barriers, even without traditional management experience, technical geniuses have the ability and will inevitably create more influential enterprises. Therefore, a16z did everything possible to attract and support these founders, bringing the innovation artist management company CAA's model into the venture capital industry. Today, being "founder-friendly" has become a popular industry concept, but at the time, this was undoubtedly a highly innovative move.

It is worth noting that in the first phase, a16z's core goal was to invest in the "right companies" and profit as these companies grew to their expected successful scale. Of course, they also focused on supporting founders, but fundamentally, the core of this phase was seizing the opportunity for "valuation arbitrage."

a16z Core Data for Partial Funds in Phase One (2009-2017)

a16z Fund III (AH III) stood out due to its simultaneous investments in Coinbase and Databricks, but what is more noteworthy is the "sustainability" of its performance.

“As a Limited Partner (LP), we are pleased to see a fund sustainably achieve a 3x (net) Total Value to Paid-in Capital ratio (TVPI), occasionally showing performance of over 5x (net) TVPI, and a16z has done just that,” said David Clark, Chief Investment Officer at VenCap (who has been an LP since a16z Fund III), “a16z is one of the few companies that can consistently deliver such performance at scale over the long term.” This can also be seen from the performance data mentioned above.

If in this phase a16z was willing to "pay a high price" and "cross over into investing like pork belly futures" to build brand reputation and wait for long-term returns, then in the short term, the cost of this "effort" seems relatively low.

Phase Two (2018-2024)

In a16z's second phase (2018-2024), its core belief shifted to: the scale of leading companies will far exceed everyone's expectations, they will remain private for longer, and the scope of technology's impact on the industry is wider than most realize.

Based on this belief, a16z took three steps to ascend from the "Top 5" to industry leaders:

Raising Larger Funds: In the first phase, a16z raised $6.2 billion through 9 funds; whereas in the second phase over five years, it raised $32.9 billion through 19 funds. The traditional VC industry consensus is "the larger the fund size, the lower the return," but a16z proposed the opposite view: if the ultimate value of leading companies will become higher, then more capital is needed to maintain a meaningful stake through multiple funding rounds. For VCs, the worst-case scenario is "missing out on leading companies" or "having insufficient ownership in already invested leading companies." Marc often says, "You can lose at most the capital you put in (i.e., 1x loss), but the upside is almost limitless."

Breaking the "Single Fund" Model, Achieving Diversified Layout: In the first phase, a16z mainly raised core funds, complemented by subsequent late-stage funds. Although each General Partner (GP) has their own focus area, all GPs invest from the same pool of funds. Furthermore, a16z has also raised a biotech fund - because the biotech sector is vastly different from other sectors. This article will focus on a16z's venture funds in non-biotech and healthcare sectors.

Upon entering the second phase, a16z began to implement a "decentralized" layout: In 2018, under the leadership of Chris Dixon, a16z launched its first cryptocurrency-focused fund, CNK I; in 2019, the company hired David George to establish a dedicated Late Stage Ventures (LSV) team and raised the largest fund at the time — LSV I with a size of $2.26 billion, approximately twice the size of any of a16z's previous funds. During this period, a16z raised multiple new funds focused on core tracks, cryptocurrency, biotech, LSV, and in 2021, introduced a dedicated seed fund (AH Seed I, $478 million), in 2022, launched a dedicated gaming fund (Games I, $612 million), as well as the first cross-strategy fund (2022 Fund, $1.4 billion) — allowing LPs to invest proportionally across all funds raised in the same year.

Importantly, although each fund can leverage the company's centralized resources (such as the investor relations team), each fund has built a dedicated platform team covering areas such as marketing, operations, finance, event planning, policy research, etc., to meet the needs of founders in specific verticals.

Extended Holding Periods: In the second phase of a16z's development, leading companies began to stay private for longer and raise more funds in the private markets — including both "primary market financing" for company operations and "secondary market transactions" to provide liquidity to employees and early investors. When a16z purchased late-stage Facebook shares in the secondary market, Matt Cohler likened this practice to "investing in pork belly futures," and today, this model has become an industry norm — companies like Stripe, SpaceX, WeWork, Uber, etc., can obtain liquidity in the private markets that was previously only available in public markets.

This trend has posed challenges for the industry: LPs find it difficult to easily obtain liquidity, disrupting the capital allocation cycle. However, for institutions that firmly believe "technology companies will significantly scale," such as a16z, this is a golden opportunity — it not only provides the opportunity to invest more capital in high-quality private companies but also shifts the returns that originally belonged to public market investors to the private markets. I believe this shift is one of the key reasons why a16z and other VC firms can significantly expand their scale without suppressing returns.

To address this trend, a16z took two key measures: first, becoming a Registered Investment Advisor (RIA), allowing for investments in cryptocurrency, public stocks, and secondary market transactions; second, under the leadership of David George, launching the aforementioned LSV I fund [9]. In the second phase, of the $32.9 billion raised by a16z, the LSV series of funds contributed $14.3 billion. Additionally, the cryptocurrency fund was also split — the fourth cryptocurrency fund (CNK IV) was divided into a seed fund ($1.5 billion) and a late-stage fund ($3 billion).

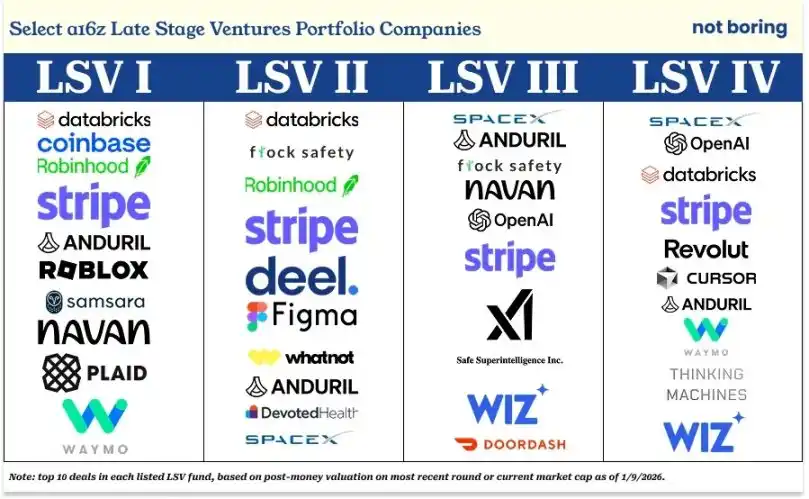

Below are the top 10 investments of each LSV fund sorted by either "Latest Round Post-Money Valuation" or "Current Market Value":

LSV I: Coinbase, Roblox, Robinhood, Anduril, Databricks, Navan, Plaid, Stripe, Waymo, Samsara

LSV II: Databricks, Flock Safety, Robinhood (exited in the public market, funds reinvested in Databricks), Stripe, Deel, Figma, WhatNot, Anduril, Devoted Health, SpaceX

LSV III: SpaceX, Anduril, Flock Safety, Navan, OpenAI, Stripe, xAI, Safe Superintelligence, Wiz, DoorDash

LSV IV: SpaceX, Databricks, OpenAI, Stripe, Revolut, Cursor, Anduril, Waymo, Thinking Machine Labs, Wiz

If, as previously accused, a16z's investments were for "riding the coattails of known companies," then the above investment portfolios are undoubtedly a "high-quality coattail list." More importantly, according to the Cambridge Association's Q2 2025 data, LSV I ranks in the top 5% among the same vintage funds, while LSV II and LSV III are also in the top 25% (i.e., the first quartile) of the same vintage funds.

As of September 30, 2025, LSV I has a Net TVPI of 3.3x; LSV II has a Net TVPI of 1.2x (however, following recent financings by Databricks and SpaceX, this number may have increased); LSV III has a Net TVPI of 1.4x (in addition, there are reports that SpaceX is about to complete a large-scale secondary market transaction, with a valuation possibly reaching $800 billion, more than double the previous valuation, so LSV III's Net TVPI is likely to further increase).

Due to the firm belief that the ultimate value of these top companies will far exceed most people's (though not everyone's — for example, Founders Fund's assessment of SpaceX, Thrive's assessment of Stripe align with a16z's), a16z has been able to invest more in these high-quality private tech companies while they are still in the private stage.

The key is that a16z has proven: under the right conditions, growth funds can also achieve venture-capital-level returns. Specifically, based on analysis data I obtained from a16z's LP, if a venture firm has strong early-stage investment capabilities and continues to add investments in the growth stage, it can not only achieve venture-capital-level returns (multiples) but also obtain a higher Internal Rate of Return (IRR). Of course, establishing a deeper partnership with these companies can further enhance a16z's industry influence.

In the second phase, a16z believes the most important goal is to "hold as much ownership of the leading companies as possible" — if it can deeply understand a company through early investments and continue to add investments through a dedicated late-stage fund (or correct early investment errors), this goal is easier to achieve (although its ownership stake has not yet reached the common "controlling" level seen in other asset classes).

The core of this phase is still "arbitrage," but unlike the first phase, a16z puts in more effort during this phase to help individual portfolio companies succeed.

Although the return period of the second-stage fund has not yet fully concluded, the performance of the second-stage fund currently outperforms that of the first-stage fund at the same time (when its performance was reported as poor by The Wall Street Journal).

a16z Fund Investment Return Performance vs. Cambridge Associates Industry Benchmark

Specifically: the 2018 vintage fund had a net TVPI of 7.3x; the 2019 fund had 3.4x; the 2020 fund had 2.4x; the 2021 fund had 1.4x; and the 2022 fund had 1.5x.

Core Performance Data of a16z's Funds from 2018 to 2024 (Second Stage)

The most noteworthy highlight of this phase is the outstanding performance of the cryptocurrency funds (CNK 1-4 and CNK Seed 1) — where CNK I has already delivered a 5.4x Net Distribution to Paid-In (DPI) return to LPs.

What's even more surprising is that despite some questioning whether a16z had "mistimed the market and overcapitalized on crypto funds" in 2022, as of now, the firm has achieved a net TVPI of 1.8x with the $3 billion raised for its Crypto Fund IV.

The two core stories of the second phase—the LSV series funds and the Crypto Fund—perfectly reflect a16z's two beliefs about the future: LSV is a response to the trend of "enterprise private cycle extension and increasing demand for private market financing," while crypto represents an idea that innovation (and returns) may come from entirely new areas outside the traditional investment track.

These two stories also highlight a16z's need to further expand its service scope—to provide support to portfolio companies while empowering the entire industry. For example, to help late-stage portfolio companies grow, a16z needs to replicate some of the public market advantages in the private market; and to ensure the survival space of the crypto industry in the U.S., and to ensure that various new technology companies can compete fairly with existing giants, a16z must move into Washington (engage in policy lobbying).

This leads to a16z's third phase (2024 onwards). In this phase, its core belief is that with a conducive environment for equitable development, new technology companies can not only reshape various industries but also succeed in all industries; and a16z must lead the industry and even the entire country in the right direction.

This belief once again changes a16z's positioning. When the company reaches a certain threshold in size (as evidenced by the $15 billion new fund raised this time), "picking winners" is no longer sufficient—

To create winners, you must shape an environment conducive to their competition.

As Ben puts it: "It's time to lead the industry."

a16z's Third Phase: It's Time to Lead the Industry

At this moment, you might be able to imagine a scenario: an analyst from a rival venture capital firm sends a message to journalist Tad Friend saying, "To achieve 5-10x returns on these two $150 billion new funds, 'you have to expand the scale of the entire U.S. tech industry by several times the existing base.'"

And you can probably guess that Marc and Ben would respond like this: Yes, that's exactly what we intend to do.

This is precisely the plan a16z has laid out, the logic being as follows:

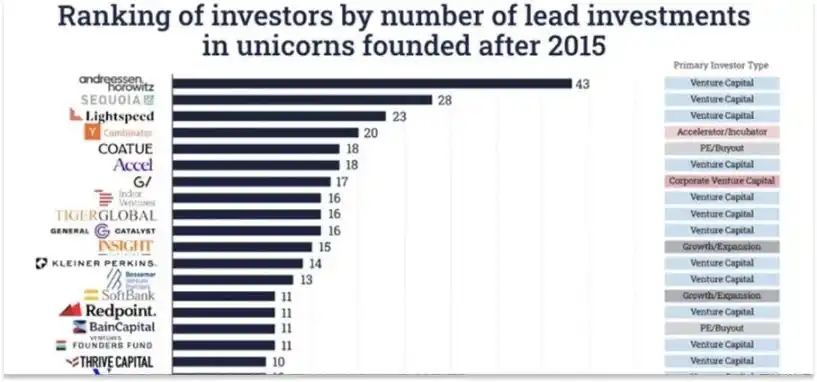

Since 2015, a16z has backed more early-stage unicorns than any other investor, and the gap between it and the second-ranked investor (Sequoia Capital) is akin to the gap between second place and twelfth place.

Source: Stanford University Professor Ilya Strebulaev

Clearly, the metric of "number of unicorns emerged among early-stage investments" serves as a very specific and convenient measure of the "top investor." While more common evaluations involve looking at returns—whether in terms of multiple returns, internal rate of return (IRR), or simply cash returned to limited partners (LPs). Some may focus on investment hit rate or performance consistency. The ways to assess venture capital industry rankings are diverse, each with its own perspective.

But this evaluation criteria centered around "unicorn count" appears to align closely with how a16z views the industry. In my conversations with the a16z crypto team, I’ve repeatedly heard a perspective like this: if many great entrepreneurs are building in a particular area, it makes sense to make bets in that area, even if the specific judgment turns out to be wrong; but missing out on the top investment in a sector, for any reason, is unforgivable. As Ben put it:

“We fully acknowledge the extremely high risks of founding a company, so as long as we follow the right process in our investments and make a reasonable risk assessment, we won't be overly concerned if some investments don't pan out. On the contrary, if we fail to accurately identify whether an entrepreneur is the best choice for their field, we take that very seriously.

Selecting the wrong emerging field is not a big deal; selecting the wrong entrepreneur is a serious issue; missing out on a great entrepreneur is equally problematic. Whether due to conflicts of interest or active decision, as long as we miss out on a company that defines the era, the consequences are far more severe than investing in the best entrepreneur in a misjudged field.”

From the "core measurement standards" that a16z itself defines, it has indeed become a leader in the venture capital industry.

“So, what's next?” Ben poses the question, “What does leading an industry truly entail?”

In a lengthy post announcing the raising of $15 billion, the X Platform provided an answer: “As a leader in the U.S. venture capital industry, the future of American new technology to some extent lies in our hands. Our mission is to ensure that America wins the technological dominance of the next 100 years.”

For a venture capital firm to say such a thing is truly rare.

However, if you agree with the following premise — that technology is the engine of progress, the U.S. must maintain its leading position by having technological superiority, a16z is the largest and most influential investor in U.S. emerging technology companies, and has the ability and resources to provide these companies with a level playing field against industry giants — then this statement is not entirely unreasonable.

Furthermore, he pointed out that to win the technological dominance of the next 100 years (which, in a16z's view, is equivalent to winning the overall leading position of the next 100 years), one must master key new technological architectures — AI and cryptocurrency — and apply these technologies to the most critical fields such as biotechnology, defense, healthcare, public safety, education, and even integrate them into government operations.

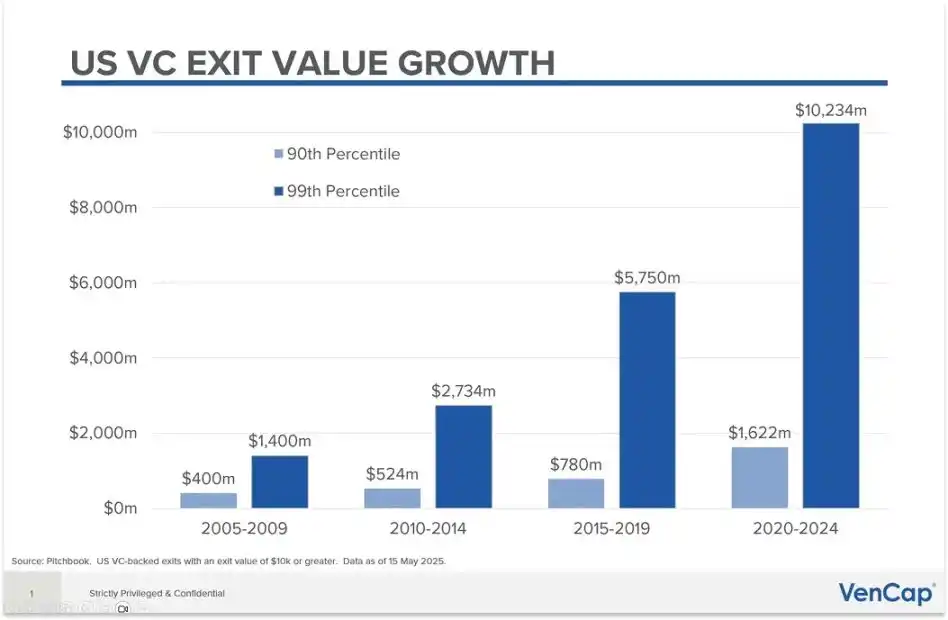

These technologies will greatly expand the market size. As I discussed in my articles “The Significant Expansion of the Tech Industry” and “Everything Can Be Technologized,” industries and tasks that were not originally within the scope of the tech industry are now included. This means that the Value Capture from Venture investment (VCAV) will also see a significant increase.

The U.S. venture capital exit scale is growing significantly, chart source: VenCap Chief Investment Officer David Clark

This is a continuation of a16z's long-standing investment strategy, but with a key ideological shift: as long as a16z fulfills its leadership responsibilities, this value can be unlocked, and the future of America (and even the world) can be secured.

Specifically, this means doing five things:

1. Reshaping U.S. technology policy to bring it back to its peak;

2. Bridging the gap between private companies and publicly traded companies;

3. Driving the marketing model towards the future;

4. Embracing new modes of corporate founding;

5. While enhancing its own capabilities, continually shaping corporate culture.

a16z's seemingly obscure moves are almost all in service of these five key goals.

Most notably, over the past two years, a16z has increasingly spoken out in the political arena, with Marc and Ben publicly supporting President Trump in the last election. This move has sparked dissatisfaction among many, with some arguing that venture capital funds should not interfere in national politics.

However, a16z would strongly oppose this view. It aims to "reshape American tech policy to put it back on top."

Marc and Ben outlined their position in the "Small Technology Business Development Agenda," with the core view being:

Emerging technology businesses are crucial for national development.

To win the future, there is a need for laws, policies, and regulatory systems that are conducive to innovation, while also preventing resource-rich industry giants from hindering competition through "regulatory capture."

However, the current situation is quite the opposite: "We believe that bad government policy has become the number one threat faced by small technology businesses."

Currently, no one is speaking up for emerging technology businesses at the government level or in the process of countering industry giants: industry giants will not do it, and startups should not invest limited resources in such affairs.

The financial gains of venture capital firms are closely tied to the success of emerging technology businesses, so the venture capital industry should rightfully carry this banner; and as a leader in the venture capital industry, a16z has an even greater responsibility.

a16z's political stance is "single-issue driven," focusing only on the development of small technology businesses and holding a bipartisan principle.

Its public positions include: "We will not participate in political disputes unrelated to small technology businesses" and "Whether we support or oppose a politician depends solely on their attitude toward small technology businesses, unrelated to their political party affiliation or positions on other issues"—from what I have seen and heard at a16z, these are not empty slogans but their true action principles.

a16z's foray into politics is not because they find it interesting (although at least Marc seems to enjoy this kind of "buzz"; he seems to be passionate about many things and can find humor in absurdity—an ability that is an underestimated competitive advantage, but we don't have time to discuss it today). In the short term, a16z is willing to endure criticism of being "foolish" and criticism from all sides just to allow emerging technology to thrive in the long term.

As former Benchmark partner Bill Gurley pointed out in "2581 Miles," for a long time, the tech industry could basically ignore Washington (referring to the U.S. government), and Washington could basically ignore the tech industry. But a few years ago, things changed, in part for the reasons I mentioned earlier—the tech industry's position has shifted from "building tools" to "competing with industry giants." And the cryptocurrency industry is the first to face "life-or-death" level regulatory pressure.

When a16z first waded into the waters of Washington, the "small tech company" was not yet a influential force in the nation's capital. Large tech companies had their own lobbying teams and government relations networks; industry titans—whether in banking, defense, or other sectors—also had their own lobbying resources and contacts. However, small tech companies, including cryptocurrency firms, did not have such support. At that time, apart from Coinbase, which may have had the capability, no small tech company could bear the cost and groundwork required to establish a representation mechanism in Washington (and in state legislatures across the U.S.).

Therefore, in October 2022, a16z's cryptocurrency team hired Collin McCune as Head of Government Affairs to lead efforts in educating U.S. policymakers about cryptocurrency. Collin, Chris Dixon, a16z's General Counsel for Crypto Miles Jennings, other team members, as well as entrepreneurs from a16z's portfolio and the entire cryptocurrency industry, made multiple trips to Washington to explain to policymakers how cryptocurrency works, its potential for development, and most importantly, the risk that overregulation could stifle emerging technologies.

These efforts have paid off. Largely due to their advocacy and the bipartisan political action committee "Fairshake SuperPAC," the cryptocurrency industry is no longer at risk of being "snuffed out" by legislation. Last year, President Trump signed the GENIUS Act, which for the first time brought stablecoins into the regulatory fold; simultaneously, a comprehensive cryptocurrency market structure bill passed the House with overwhelming bipartisan support and is currently being considered by the Senate, with prospects for passage and enactment later this year.

This experience has been instrumental as artificial intelligence has become a focal point in Washington. Today, McCune leads all of a16z's government affairs efforts, establishing a permanent presence in Washington working across multiple domains including AI, cryptocurrency, and American Dynamism. Currently, a16z is advocating for the establishment of unified federal AI regulatory standards to avoid regulatory policy fragmentation across states and to push for other innovation-friendly policies.

Although the term "lobbying" may carry negative connotations, the current reality is that competitors of small tech companies have mature government affairs and policy teams that are seeking to make it difficult for new entrants to compete fairly through "regulatory capture."

In order for the tech industry to win the future, and for a16z's funds to see returns, staying out of politics is no longer a viable option. The good news is that a16z's survival depends on the founding, growth, and success of emerging companies, making it more incentivized than any entity to uphold a fair competitive environment conducive to innovation.

Because even a16z itself acknowledges that, standing here today, no one can predict what future companies will emerge, nor how they will emerge.

The idea of "embracing a new model of company creation" means recognizing the possibility that, with the help of AI technology, the number of employees needed for a founder to start a company in the future may be only 1/10 or even 1/100 of what it was in the past, and the elements needed to build a great company may also be drastically different from before. This also means that a16z itself needs to adjust.

For example, a16z has launched an internal accelerator program called "Speedrun": providing up to $1 million investment to startups and conducting a 12-week incubation program. Through this initiative, a16z can gain early insights into the founding models of these new types of companies, thoroughly examine each participating company, and thus more wisely make follow-on investments in potential companies.

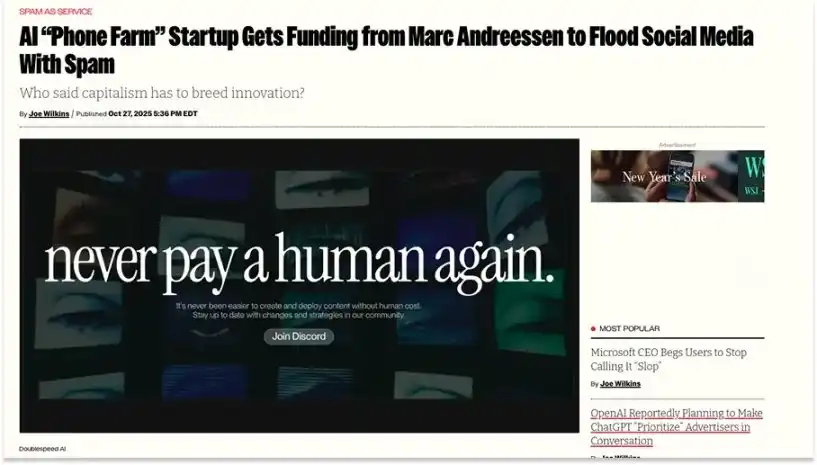

However, this move also comes with risks: increasing the number of companies that can claim to be "backed by a16z," lowering the investment threshold, may dilute a16z's brand credibility. For instance, a16z sparked controversy on Platform X for investing in a company called Doublespeed through the Speedrun program — the company claimed to provide "synthetic creator infrastructure," but others accused it of being a "phone farm" and "trash information as a service."

Source: Futurism

Some argue that "the company received investment from Marc Andreessen," which is rather ironic — because Marc does not participate in individual decisions for Speedrun projects of less than $1 million, considering each Speedrun investment accounts for only about 0.001% of a16z's assets under management (AUM). But this precisely highlights the core issue: I have seen many references on Platform X to this "a16z-backed company," until later assuming it might be a project from Speedrun incubation and then verifying it. However, most people will not take the time to fact-check this.

Another more controversial similar case is the startup Cluely, which claims to "help users cheat in various transactions," and a16z led a $15 million investment in the company through its AI application fund.

People have reason to question: as an institution dedicated to shaping the future of America, why would a16z invest in a company that prioritizes "viral spread" over "ethical standards"? In the eyes of those active on the internet, does having a company like Cluely in the portfolio weaken the credibility of all other invested companies?

The answer is likely yes. Personally, I do not agree with this investment decision—it gives off a "lowbrow" and "undignified" feeling.

However! From a16z's own logic, this decision is consistent.

Because setting aside the product itself, the core message conveyed by Cluely is: in the age of artificial intelligence, the enterprise founding model is undergoing a fundamental shift—its premise being that the ability of underlying models is trending towards convergence and commodification, thus "spreadability" will become the sole key factor; and in order to achieve spread, a little controversy is inconsequential.

If a16z is truly committed to "embracing a new model of enterprise founding," then using $15 million and a minor X platform controversy to exchange for a "front-row seat" to observe an extremely innovative enterprise founding model is actually not a high price.

More broadly, in the industry where a16z operates, occasionally "appearing foolish" is a necessary cost to avoid repeating Kodak's mistakes. Enterprises must be willing to take risks, and these risks go far beyond the financial aspect. For a company of a16z's scale, investing a small amount of money is actually the lowest-risk way to take a gamble.

However, there is also a view that, from a global perspective, these minor controversies on the X platform (which is also an a16z portfolio company) are irrelevant. In fact, when I asked a16z General Partner Katherine Boyle (who is also a co-founder of the company's "American Renaissance" business) about this issue, she expressed this view:

"You might say, yes, we do receive some criticism on the X platform because of certain companies—like people in a certain circle in San Francisco or New York not liking a particular company, they might say 'We don't like them doing 'American Renaissance' business! We don't like them doing cryptocurrency!'

But in terms of the overall scale of our system, these momentary minor controversies are inconsequential.

The top-tier institutions all have a scaled system, just like a country such as America. When America makes some embarrassing moves on the global stage, do we care? No, because it doesn't have a substantial impact on America, just like similar events do not affect the Catholic Church."

Our unit of analysis is the 'century', not a 'single tweet'."

You may not agree with all of a16z's practices, but you have to admire the guts of this firm.

Notably, when I asked some of a16z's LPs about these controversial X-platform-triggering businesses, their reaction was often a blank face asking, "Who?"—evidently, they had never heard of these companies.

For a16z's returns, what truly matters has always been the "flagship companies": spotting them early, successfully participating in their financing transactions, and holding onto as much equity as possible in the long run. If you were to ask any a16z LP about Databricks, they would surely be familiar with it.

Now, in the "leading the industry" third phase, there is another equally crucial thing: even as these flagship companies have significantly expanded, helping them continue to grow.

I believe this is the essence of what Ben calls "filling the gap between private and public company development"—this is also the key perspective reshaping our current understanding of a16z's positioning and how it is poised to deliver 5-10x returns on its $15 billion fund.

Ben stated: "In the past, venture capitalists would help companies achieve $100 million in revenue, then hand them over to investment banks to take the company public." But those days are gone. Today's companies not only stay private longer but are also much larger—meaning the venture capital industry, represented by a16z, needs to enhance its capabilities to meet the development needs of larger companies.

To that end, a16z recently hired former VMware CEO Raghu Raghuram, giving him a "triple role": serving as a general partner for the AI infrastructure team led by Martin Casado, a general partner for the growth investment team led by David George, and also serving as a managing partner as Ben's "advisor to help operate the firm." Raghu will co-lead a series of new initiatives with Jen Kha to "meet the needs of large companies in their growth stages."

Specifically, these initiatives include: collaborating with governments worldwide to help portfolio companies achieve scale and market expansion locally; forming strategic partnerships with companies like Eli Lilly (who have jointly launched a $500 million biotech ecosystem fund); expanding the number and depth of limited partner (LP) relationships globally; and expanding the services of the a16z Executive Briefing Center—a center that offers customized services to large companies, allowing them to directly connect with companies in a16z's portfolio in relevant areas.

Even for large corporations, some resources, if each company were to build them from scratch individually, would be neither realistic nor cost-effective. However, having a16z centrally build these resources and distribute them across the entire portfolio is a reasonable choice. And these resources happen to involve government-level matters, trillion-dollar-scale companies, and trillions of dollars in capital.

All of these measures could allow companies to stay private without sacrificing the credibility, partnerships, or financing channels that public companies have.

This means that companies can grow to a larger scale in the private markets—a core coverage area for a16z.

It also means that a16z has the opportunity to deploy more capital with a reasonable probability of receiving generous returns; and more returns can then translate into more resources to enhance its capabilities, strengthen its industry influence—these capabilities and influence can further empower its portfolio companies, and even gradually empower the entire emerging tech industry, thus driving more and higher-quality new technologies to be applied in more areas of the economy, ultimately enabling everyone to have a better future.

Of course, there are bound to be many risks in the process. "More money, more problems," leaders always have to endure more criticism, and so on.

In my opinion, a16z is engaging in industry competition at an unprecedented breadth and scale, which presents both opportunities and risks.

For example, the broader the business coverage, the more potential risk points there naturally are. In theory, the longer a company remains private, the more challenging it is to create liquidity for limited partners (LPs); the difficulty for LPs to invest in new funds will also increase, and these new funds are the financial foundation for a16z to invest in future potential giants.

However, in the end, two core groups determine everything: founders and LPs—they are both the company's clients and investors.

The Two Key Groups: LPs and Founders

Founders' choices of which institution's investment to accept and LPs' choices of which institution to fund, their attitudes toward a16z, precisely encapsulate all the core logic I discussed earlier.

My analytical logic is as follows:

If the top founders believe that the system a16z has built can help them create a larger company than through other means, then they will prioritize a16z's investment (or at least ensure that a16z is one of their funding sources).

If LPs believe that a16z will continue to invest in the best founders, then even in the face of a liquidity crisis, they will prioritize funding a16z and hold its fund shares for the long term.

During my conversation with Jen Kha, she shared a story that clearly illustrated: in the venture capital industry, "investing in the very best companies" (assuming you pick the right race) is the only key thing.

A few years ago, during a brief venture capital downturn, the market faced both liquidity concerns and uncertainty due to the Trump administration's unclear stance on the tax status of donation funds. At that time, a16z took the initiative to offer liquidity support to LPs. Looking back at the news coverage from that time—including rumors about top donation funds selling off their venture portfolios—it's easy to see that a16z's move was like offering a drink of water in the desert.

Specifically, a16z's Fund I held Stripe's seed round shares, and Fund III acquired a large stake in Databricks' Series A financing. a16z told LPs, "We know you are facing a liquidity crisis. If you're willing, we can buy back your shares in these companies to create some liquidity for you."

"Packy, here's the situation," Jen recalled, "All 30 LPs replied 'absolutely not considering.' They said, 'Thank you for your kindness, but we don't want to cash out from these companies' shares; we want to cash out from shares of other companies.'

As an LP of a16z, David Clark, Chief Investment Officer of VenCap, explained, "The essence of venture capital is not short-term liquidity but long-term compounding growth. We do not want the fund manager to sell off the highest-quality company shares too early."

Anne Martin of Wesleyan University was one of these 30 early LPs, and her investment experience also confirms the power of compounding. Since the establishment of a16z's Fund I in 2009, she has been supporting the organization—back then she was working at the Yale endowment; now as Chief Investment Officer of Wesleyan University, she has participated in 29 of a16z's funds. The latest fund raised by a16z will make this number exceed 30.

"In the portfolio I lead investments in, a16z not only has a significant position size but also is the longest-held asset," Anne said last month when I spoke with her, "At the first investment committee meeting I hosted after joining, I recommended two new fund managers to the committee members, and a16z was one of them."

Initially, Anne invested in a $300 million fund—Jen said, "She directly negotiated the Limited Partner Agreement (LPA) terms with Ben." Anne agrees with a16z's view that the "market opportunity is sufficient to support a larger fund size."

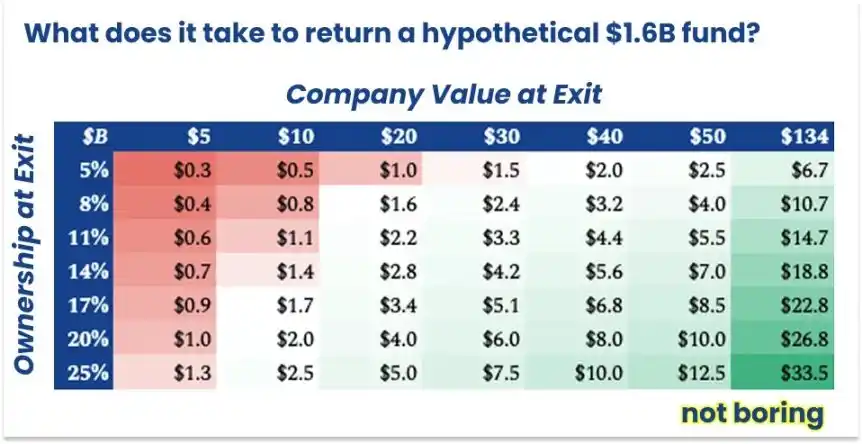

「The special thing about a16z is... Taking their $1.6 billion AI infrastructure fund as an example, you can simply set up a matrix calculation: 'Assuming they hold 8% ownership at exit... What exit valuation is needed to return the fund?' Holding an 8% ownership stake would require the company to exit at a valuation of $20 billion. While such a scenario is not common, a16z seems to hit many of these. What is more noteworthy is whether the 8% ownership stake is reasonable for them? Because many times, their ownership stake is much higher.」

For illustrative purposes only... but indeed feasible

「I think, for them, the key is the ownership stake and the ability to help these companies achieve massive outcomes,」 Anne told me, 「It is these two points that make LPs confident in a large fund.」

It is also this ability to 'help companies achieve massive outcomes' that even the most sought-after founders are willing to offer a16z more favorable investment terms than other competitors. In just 2025 alone, there were multiple transactions where a16z invested at a valuation lower than other top-tier firms in the round. While I can't disclose specific company names, I learned that just last year, four well-known technology companies used this model during their fundraising.

In fact, founders highly appreciate the resources a16z can provide, so they are sometimes willing to accept valuations below market levels. This is a stark contrast to a16z's early days–at that time, competitors, unhappy with a16z's frequent high-priced competitive bidding, even gave it the nickname 'A-Ho.' The change today is enough to prove that working with a16z can bring real and tangible value, and companies are willing to accept a 'higher dilution ratio' as an exchange.

This means that although I mentioned two key groups earlier, ultimately, there is only one core group: if the very best founders are willing to work with a16z, the highest-quality LPs will naturally follow suit.

Can a16z enhance the development outcomes of its portfolio companies?

This is the core question, isn't it? We can express this with a hypothetical formula:

a16z's contributed market value percentage × Total affected market value

The key challenge of this formula is: in order to significantly increase the left-hand side's "Contribution Percentage," you must provide help when the right-hand side's "Total Addressable Market Value" is at its lowest (i.e., in the early stages of the company).

However, when you truly help a small business grow into an industry giant, the loyalty you receive is priceless—the founders will actively recommend you to other founders considering funding and will also speak up for you in media coverage.

Previously, I asked Erik Torenberg to help me connect with some a16z-backed founders. Within a few hours, he introduced me to founders of companies with a total market value of over $200 billion, including Ali Ghodsi of Databricks and Garrett Langley of Flock Safety.

I specifically mentioned these two founders because within 48 hours of connecting with them, two significant events occurred: Databricks announced a $40 billion funding round, reaching a valuation of $134 billion, and Flock Safety assisted in capturing the suspect involved in the murder of individuals associated with Brown University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). These two events vividly demonstrate the influence of a16z-backed companies.

Source: Boston.com and The Wall Street Journal

But what I really want to understand is: how does a16z leverage its influence to support these companies? Has this support truly altered the trajectory of these companies? Has the resource ecosystem constructed by a16z, involving investments of hundreds of millions or even billions of dollars, really brought about significant changes for these companies?

To believe in a16z's wager in the third phase—namely, expanding the market size of tech startups, increasing the value of funded companies, and generating substantial returns for its $15 billion new fund—you may first need to believe that the answers to the above questions are affirmative.

And indeed, the answer is affirmative.

Recall that Ali from Databricks once stated: "Without a16z, there would be no Databricks today." With just this one company, it has added $134 billion (and counting) in value to the venture-investable market and brought about a net return of around $20 billion to a16z. Even if his statement is somewhat exaggerated, it is not difficult to argue: a16z's support for Databricks—from early sales assistance, facilitating collaboration with Microsoft, to helping establish specific departments—has already covered the value of all a16z's investments in platform building since its inception.

In fact, we can make an assumption: if a16z currently still holds about 15% of Databricks, a rough calculation shows that as long as a16z's contribution to Databricks' valuation reaches around 25%, it will cover the regular venture capital management fees it has charged since its inception.

All the founders I have interviewed have mentioned a consistent working model at a16z—a shadow of the innovative talent agency CAA—where no matter which General Partner (GP) you are working with, this model clearly shows: they do not intervene when not needed, allowing you to autonomously run your business; once you express a need, they will "all hands on deck" to provide support.

This is also the key way a16z wins investment deals: each fund's GP is responsible for deciding on investment targets, and when needed, they will mobilize all company resources—including Marc and Ben themselves—to vigorously pursue the deal.

"The ideal state of the company is 'delegated authority, shared belief, collaborative determination,'" David Haber told me, "Marc will basically say, 'As long as you tell me this is the next Coinbase, I am willing to fly anywhere in the world. I can invite this entrepreneur to my house for dinner tonight. Act immediately, at any cost.'"

After the deal is completed, the collaboration model between the GP and the founder remains the same.