Why Does Hyperliquid Earn Less Than Coinbase?

Original Title: Hyperliquid at the Crossroads: Robinhood or Nasdaq Economics

Original Author: @shaundadevens

Translation: Peggy, BlockBeats

Editor's Note: As Hyperliquid's trading volume approaches that of traditional exchanges, what is truly worth paying attention to is no longer just "how large the volume is," but rather where it chooses to position itself within the market structure. This article uses the traditional finance division of "Brokerage vs. Exchange" as a reference point, analyzing why Hyperliquid has proactively adopted a low-fee market layer positioning, and how Builder Codes, HIP-3, while expanding the ecosystem, exert long-term pressure on platform fees.

Hyperliquid's path reflects the core issue that the entire crypto trading infrastructure is facing: how to allocate profits after achieving scale.

The following is the original text:

Hyperliquid is handling perpetual contract trading volumes close to Nasdaq levels, but its profit structure also exhibits "Nasdaq-level" characteristics.

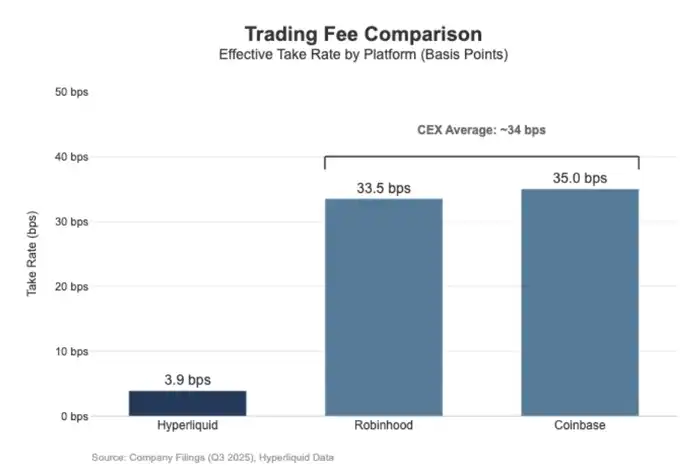

In the past 30 days, Hyperliquid has cleared $205.6 billion in perpetual contract nominal trading volume (quarterly annualized approximately $617 billion), but has generated only $8.03 million in fee revenue, equivalent to a fee rate of about 3.9 basis points (bps).

This means that Hyperliquid's revenue model is more similar to a wholesale execution venue rather than a high-fee retail trading platform.

For comparison, Coinbase recorded $295 billion in trading volume in Q3 2025, but achieved $1.046 billion in trading revenue, implying a fee rate of about 35.5 basis points.

Robinhood's monetization logic in the crypto business is similar: its $80 billion in nominal crypto asset trading volume resulted in $268 million in trading revenue, implying a fee rate of about 33.5 basis points; meanwhile, Robinhood's stock nominal trading volume in Q3 2025 was as high as $647 billion.

Overall, Hyperliquid has emerged as a top-tier trading infrastructure in terms of trading volume. However, in terms of fees and business model, it resembles more of a low-fee execution layer targeting professional traders rather than a retail-oriented platform.

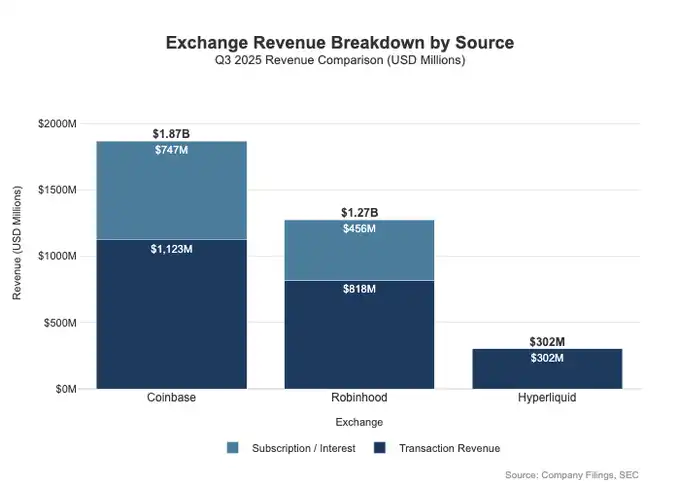

The difference is not only evident in the fee levels but also in the breadth of monetization dimensions. Retail platforms are often able to profit from multiple revenue "streams" simultaneously. In the third quarter of 2025, Robinhood generated a total of $7.30 billion in transaction-related revenue, in addition to $4.56 billion in net interest revenue, and $88 million in other revenue (mainly from Gold subscription services).

In contrast, Hyperliquid currently relies much more on trading fees, and these fees are structurally compressed at single-digit basis points at the protocol level. This means that Hyperliquid's revenue model is more concentrated, more singular, and closer to a low-fee, high-turnover infrastructure role, rather than a retail platform with deep monetization through multiple product lines.

This can be fundamentally explained by positioning differences: Coinbase and Robinhood are brokerage/distribution businesses that leverage their balance sheets and subscription systems for multi-layered monetization; while Hyperliquid is closer to the exchange layer. In the traditional financial market structure, the profit pool is naturally split between these two layers.

Broker-Dealer vs. Exchange Model

In traditional finance (TradFi), the most core distinction lies in the separation of the distribution layer and the market layer.

Retail platforms like Robinhood and Coinbase are positioned in the distribution layer, able to capture high-margin monetization surfaces; while exchanges like Nasdaq are positioned in the market layer, where their pricing power is structurally constrained, and execution services are competitively pushed towards a commoditized economic model.

Broker/Dealer = Distribution Capabilities + Customer Balance Sheet

Broker-dealers hold the customer relationships. Most users do not directly access Nasdaq but enter the market through broker-dealers. Broker-dealers are responsible for account opening, custody, margin and risk management, customer support, tax documents, etc., and then route orders to specific trading venues.

It is this "relationship ownership" that allows broker-dealers to engage in multi-layered monetization beyond trading:

Funds and Asset Balance: Cash Aggregation Interest Rate Spread, Margin Lending, Securities Lending

Product Bundling: Subscription Services, Feature Packages, Bank Cards / Wealth Management Products

Routing Economics: Brokerage Firm controls order flow, can embed payment or revenue-sharing mechanisms in the routing chain

This is also why brokerage firms often earn more than trading venues: the profit pool is truly concentrated in the position where "distribution + balance" resides.

Exchange = Matching + Rules + Infrastructure, Limited Fees

Exchanges operate the trading venue itself: matching engine, market rules, deterministic execution, and infrastructure connections. Its main monetization methods include:

Trading Fees (continuously suppressed in high-liquidity products)

Rebates / Liquidity Incentives (often to compete for liquidity, most of the nominal fee rate is returned to the market maker)

Market Data, Network Connections, and Colocation

Listing Fees and Index Licensing

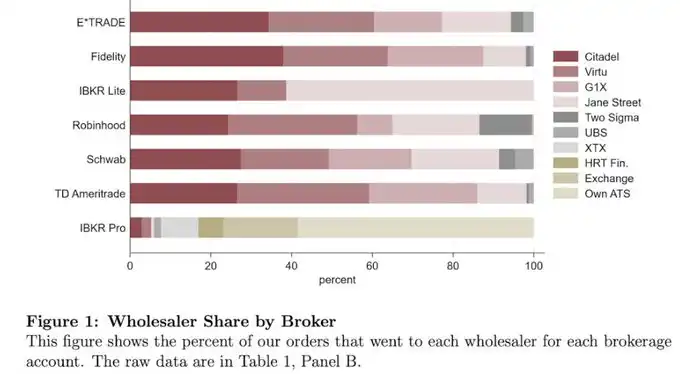

Robinhood's order routing mechanism clearly illustrates this structure: the customer relationship is held by the brokerage firm (Robinhood Securities), and orders are then routed to third-party market centers, with economic interests distributed in the chain during the routing process.

The real high-margin layer is at the distribution end, which controls customer acquisition, customer relationships, and all monetization aspects surrounding execution (such as order flow payment, margin, securities lending, and subscription services).

The Nasdaq itself is in the low-margin layer. The products it provides are essentially highly commoditized execution capability and queue access rights, and its pricing power is strictly limited in mechanism.

The reason is that: to compete for liquidity, trading venues often need to massively return the nominal fees as maker rebates; at the regulatory level, there are limits on access fees, limiting the fee space that can be charged; at the same time, order routing has high elasticity, funds and orders can quickly switch between different trading venues, making it difficult for any single venue to raise prices.

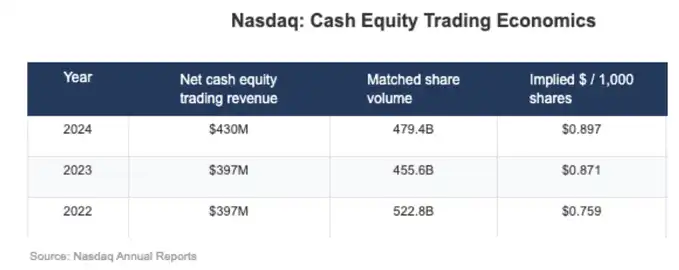

In Nasdaq's disclosed financial data, this is very intuitively reflected: the actual net revenue captured in cash stock trading is usually only at the level of a fraction of a cent per share. This is a direct representation of the structural compression of the market-level exchange profit space.

The strategic consequences of this low-profit-margin environment are also clearly reflected in Nasdaq's revenue structure shift.

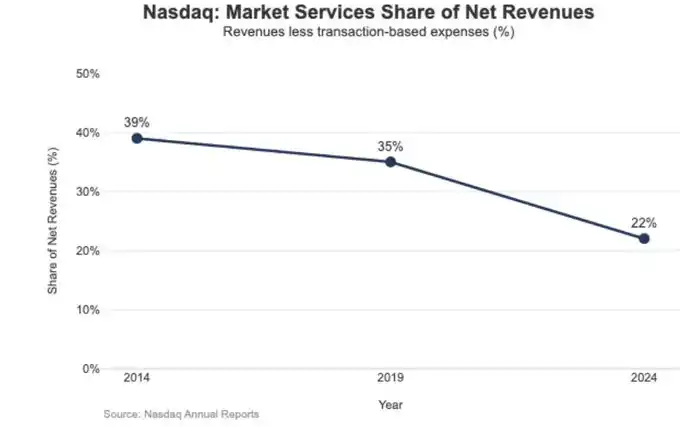

In 2024, Nasdaq's Market Services revenue was $1.02 billion, accounting for 22% of the total revenue of $4.649 billion, a proportion that was as high as 39.4% in 2014 and still 35% in 2019.

This continued downward trend is highly consistent with Nasdaq's proactive shift from a highly market-volatile, profit-constrained execution business to a more recurring and predictable software and data business. In other words, it is the structurally limited profit space at the exchange level that has driven Nasdaq to gradually shift its growth focus from "matching and execution" to "technology, data, and service-oriented products."

Hyperliquid as a "Market Layer"

Hyperliquid's approximately 4 basis points (bps) effective fee rate aligns closely with its intentionally chosen market layer positioning. It is building an on-chain "Nasdaq-style" trading infrastructure:

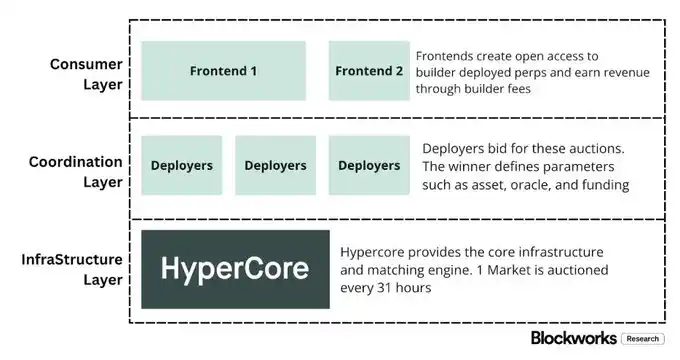

A high-throughput matching, margin, and clearing system centered around HyperCore, using maker/taker pricing and market-making rebate mechanisms, aims to maximize execution quality and shared liquidity rather than conducting multi-layer monetization for retail users.

In other words, Hyperliquid's design focus is not on subscription, balance, or distribution-type revenue but on providing commoditized yet extremely efficient execution and settlement capabilities—this is the typical characteristic of the market layer and an inevitable result of its low-fee structure.

This is evident in the structural split that is very typical in traditional finance (TradFi) but has not yet fully materialized in most cryptocurrency trading platforms:

One is the permissionless brokerage/distribution layer (Builder Codes).

Builder Codes allow third-party trading interfaces to be built on top of the core exchange and earn economic benefits independently. The Builder fees have a clear upper limit: a maximum of 0.1% (10 basis points) for perpetual contracts and 1% for spot, and fees can be set at the order level. This mechanism has created a competitive market in the distribution layer, rather than a single official app monopolizing user access and monetization rights.

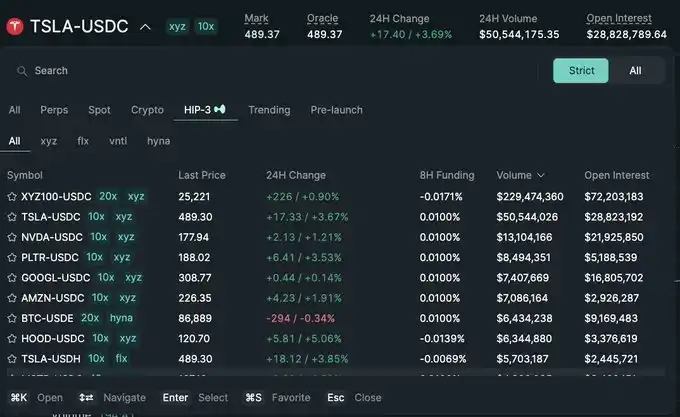

Second, Permissionless Listing / Product Layer (HIP-3).

In traditional finance, exchanges usually control listing approval and product creation. HIP-3 externalizes this function: developers can deploy a perpetual contract inheriting the HyperCore matching engine and API capabilities, while the definition and operation of a specific market are the responsibility of the deployer.

In terms of the economic structure, HIP-3 explicitly defines the revenue-sharing relationship between the exchange and the product layer: the deployers of spot and HIP-3 perpetual contracts can retain up to 50% of the asset's trading fees they deploy.

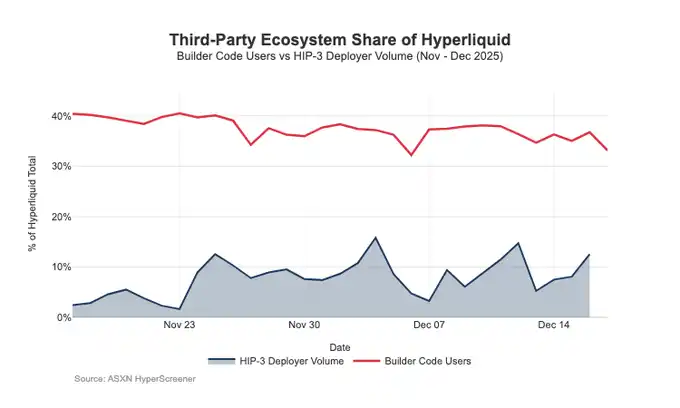

Builder Codes have already demonstrated their effectiveness on the distribution side: as of mid-December, approximately one-third of users did not trade through the native interface but through a third-party frontend.

The issue is that this structure, which favors distribution expansion, will also exert continuous pressure on the exchange layer's fees:

1. Price Compression.

Multiple frontends simultaneously selling the same underlying liquidity will naturally lead to price convergence towards the lowest total transaction cost; and Builder fees can be flexibly adjusted at the order level, further driving prices to the lower limit.

2. Loss of Realization.

Frontends control onboarding, product packaging, subscription services, and the complete trading workflow, thus capturing the high gross margin space of the brokerage layer; while Hyperliquid can only retain a thinner exchange layer fee.

3. Strategic Routing Risk.

Once the frontend evolves into a true cross-exchange router, Hyperliquid may be forced into wholesale execution competition, only able to defend order flow through fee reduction or increased rebates.

Overall, Hyperliquid is consciously choosing a low-profit margin market layer positioning (through HIP-3 and Builder Codes), while allowing a high-profit margin brokerage layer to grow on top of it.

If Builder frontends continue to expand, they will increasingly dictate the user-facing pricing structure, control user retention and monetization interfaces, and gain bargaining power at the routing layer, structurally exerting long-term pressure on Hyperliquid's fee rate.

Defend Distribution Rights and Introduce a Non-Exchange Profit Pool

The most direct risk is commoditization.

If a third-party frontend can consistently undercut the native interface in price and eventually achieve cross-venue routing, Hyperliquid will be pushed towards a wholesale execution-oriented economic model.

Recent design adjustments show that Hyperliquid is trying to explore new revenue streams while avoiding this outcome.

Distribution Defense: Maintaining the Economic Competitiveness of the Native Frontend

A previously proposed staking discount scheme allows Builders to stake HYPE to receive up to a 40% fee discount, effectively providing a structurally cheaper path for third-party frontends compared to the Hyperliquid native interface. The withdrawal of this scheme is equivalent to eliminating the direct subsidy for external distribution's "price pressure."

At the same time, HIP-3 markets, initially positioned to be primarily distributed through Builders and not featured on the main frontend, have now started to be showcased in Hyperliquid's native frontend with strict listing standards.

This signal is crystal clear: Hyperliquid still maintains permissionless at the Builder layer but will not sacrifice its core distribution rights at the expense of external distributors.

USDH: Shifting from Transactional Realization to "Float" Realization

The launch of USDH aims to reclaim the stablecoin reserve yield that would have originally been captured outside the system. Its transparent structure offers a 50/50 revenue split from the reserve yield: 50% to Hyperliquid and 50% for USDH's ecosystem growth.

Additionally, the transaction fee discounts provided for USDH-related markets further reinforce this orientation: Hyperliquid is willing to forego single transaction economics in exchange for a larger, stickier, balance-bound profit pool.

Effectively, this is akin to introducing a pension-like income source for the protocol, the growth of which depends on the monetary base scale rather than just nominal trading volume.

Portfolio Margin: Introducing a Prime Broker-like Financing Economics

Portfolio Margin unifies the collateral of spot and perpetual contracts, allowing different exposures to offset each other and introducing a native lending loop.

Hyperliquid will retain 10% of the interest paid by borrowers, making the protocol's economics increasingly dependent on leverage utilization rates and interest rate levels rather than just trading volume. This is closer to a brokerage/prime broker's revenue model rather than a pure exchange logic.

Hyperliquid's Path to a "Brokerage-Style" Economic Model

On the throughput front, Hyperliquid has already reached the scale of Tier-1 exchanges; however, in terms of monetization, it still resembles a market layer: with extremely high nominal trading volumes, coupled with a single-digit basis points effective take rate. The gap with platforms like Coinbase and Robinhood is structural.

Retail platforms sit at the brokerage layer, holding user relationships and fund balances, able to monetize multiple profit pools simultaneously (margin, idle cash, subscriptions); whereas pure exchanges sell execution services, which, under liquidity and routing competition, naturally commoditize execution, with net captures being continuously compressed. Nasdaq is the TradFi reference of this constraint.

Hyperliquid early on notably leaned towards the exchange prototype. By splitting the distribution layer (Builder Codes) and the product creation layer (HIP-3), it accelerated ecosystem expansion and market coverage; however, the cost is that this architecture may also push the economics outward: once third-party frontends decide on best price aggregation and can route across venues, Hyperliquid risks being squeezed into a low-margin wholesale execution track.

However, recent actions show a conscious shift: without giving up the unified execution and clearing advantage, defending the distribution right, and expanding revenue sources to a "balance-driven" profit pool.

Specifically: the protocol is no longer willing to subsidize external frontends structurally cheaper than the native UI; HIP-3 is more native-focused; and an asset-liability-style revenue source is introduced.

USDH brings reserve income back to the ecosystem (split fifty-fifty, and provides fee discounts for the USDH market); portfolio margin introduces finance economics through a 10% cut on borrowing interest.

Overall, Hyperliquid is converging towards a hybrid model: with an execution track as the base, adding distribution defense and balance-driven profit pools on top. This reduces the risk of being trapped in a low-basis point, wholesale exchange, while moving closer to a brokerage-style revenue structure without sacrificing the advantages of unified execution and clearing.

Looking ahead to 2026, the pending question is: Can Hyperliquid further move towards a brokerage-style economy without disrupting its "outsourcing-friendly" model? USDH is the clearest litmus test: at around a $100 million supply level, expansion of outsourced issuance appears sluggish when the protocol does not control distribution.

The obvious alternative path could have been UI-level defaults—such as automatically converting the approximately $40 billion USDC balance into a native stablecoin (similar to Binance's automatic conversion of BUSD).

If Hyperliquid wants to truly tap into the broker layer profit pool, it may also need broker-like behaviors: stronger control, tighter native product integration, and clearer boundaries with the ecosystem team on distribution and balance competition.

Welcome to join the official BlockBeats community:

Telegram Subscription Group: https://t.me/theblockbeats

Telegram Discussion Group: https://t.me/BlockBeats_App

Official Twitter Account: https://twitter.com/BlockBeatsAsia